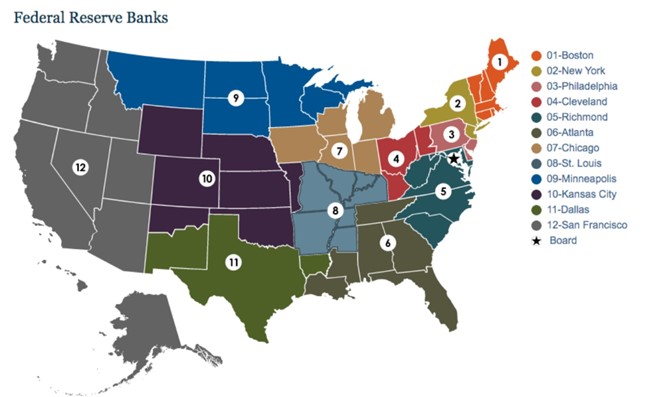

The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has implemented a major shift in the $26 trillion US Treasury market, adopting new regulations aimed at reducing systemic risk by forcing more trades through clearing houses. This overhaul, approved on December 13th, 2023, marks the most significant change to this global benchmark for assets in decades.

The Need for Reform:

In recent years, the Treasury market has experienced periods of volatility and liquidity concerns. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 highlighted these vulnerabilities, as liquidity all but evaporated during the initial market panic. This prompted calls for reform, with the SEC identifying the need to increase transparency and reduce counterparty risk.

Central Clearing: The Centerpiece of Reform:

The core of the SEC’s new rules revolves around central clearing. A central clearinghouse acts as the intermediary for every transaction, assuming the role of both buyer and seller. This ensures that trades are completed even if one party defaults, significantly minimizing risk.

The new regulations mandate that a broader range of Treasury transactions now be centrally cleared. This includes cash Treasury transactions as well as repurchase agreements (“repos”), which are short-term loans backed by Treasuries. Additionally, clearing houses must implement stricter risk management practices and maintain separate collateral for their members and their customers.

Phased Implementation:

Recognizing the complexity of implementing such a significant change, the SEC has provided a phased approach. Clearing houses have until March 2025 to comply with the new risk management and asset protection requirements. They will have until December 2025 to begin clearing cash market Treasury transactions and June 2026 for repo transactions. Similarly, members of clearing houses have until December 2025 and June 2026, respectively, to begin clearing these transactions.

Industry Concerns and Potential Impact:

While the SEC’s initiative aims to enhance the safety and stability of the Treasury market, some industry participants have voiced concerns. The primary concern revolves around the potential increase in costs associated with central clearing. Clearing houses charge fees for their services, which could be passed on to market participants. Additionally, the requirement for additional margin, which serves to limit risk, could also lead to higher costs.

Another concern is the potential impact on liquidity. Some critics argue that mandatory clearing could lead to a decrease in liquidity, particularly during times of market stress. This is because central clearing adds another layer of bureaucracy to the transaction process, which could discourage some market participants from trading.

Furthermore, there are concerns about the potential concentration of risk in clearing houses. If a major clearing house were to fail, it could have a devastating impact on the entire financial system. To mitigate this risk, the SEC has implemented stricter capital and risk management requirements for clearing houses.

The Road Ahead:

The implementation of these new regulations will undoubtedly impact the US Treasury market. While the long-term effects remain to be seen, the SEC’s goal is to create a safer and more resilient market for all participants. The phased approach allows for a smoother transition, giving market participants time to adjust to the new requirements.

The success of these reforms will depend on several factors, including the effectiveness of implementation by clearing houses and market participants, the ongoing monitoring and oversight by the SEC, and the overall economic environment. Only time will tell whether these changes will achieve their intended goal of enhancing the stability and efficiency of the US Treasury market.

Additional Considerations:

The SEC’s decision to exempt certain transactions, such as those between broker-dealers and hedge funds, has garnered mixed reactions. Some argue that this creates loopholes and undermines the effectiveness of the reforms. Others contend that it is a necessary concession to address industry concerns and avoid stifling market activity.

The implementation of these new rules will also require close collaboration between the SEC, clearing houses, and market participants. Clear communication and education will be essential to ensuring a smooth transition and maximizing the benefits of these reforms.

Ultimately, the success of these changes will hinge on their ability to strike a delicate balance between enhancing safety and maintaining market efficiency. Only time will tell if this major overhaul of the US Treasury market will ultimately achieve its intended objectives.