Will Systemic Risks to the Banking System Override Inflation Concerns When the Fed Meets?

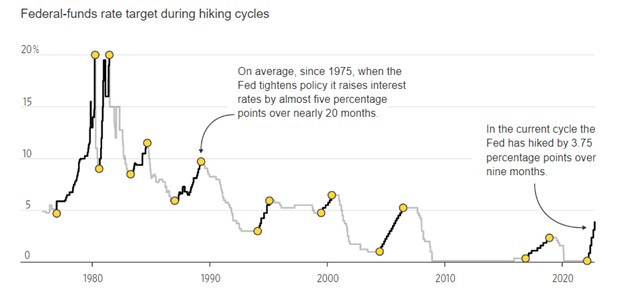

Yes, the Federal Reserve’s central objective is to help maintain a sound banking system in the United States. The Fed’s regional presidents are currently in a blackout period (no public appearances) until after the FOMC meeting ends on March 22. So there is little for markets to go on to determine if the difficulties being experienced by banks will hinder the Fed’s resolve to bring inflation down to 2%. Or if the systemic risks to banks will override concerns surrounding inflation. Below we discuss some of the considerations the Fed may consider at the next meeting.

The Federal Reserve’s sound banking system responsibility is part of its broader responsibility to promote financial stability in the U.S. economy. The Fed does its best to balance competing challenges through monetary policy to promote price stability (low-inflation), maintaining the safety and soundness of individual banks, and supervising and regulating the overall banking industry to ensure that it operates in a prudent and sound manner.

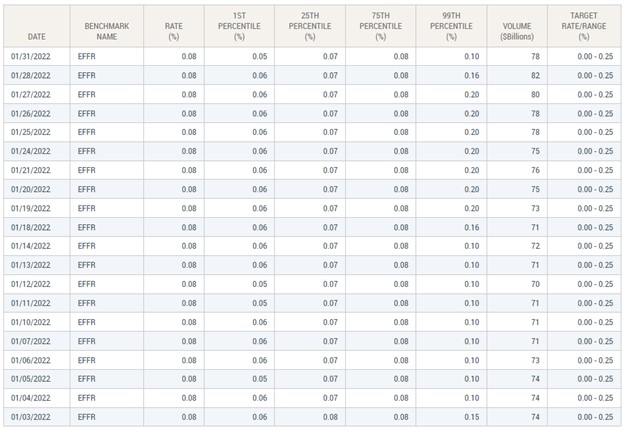

While the headline news after the Fed adjusts monetary policy is usually about the Fed Funds target, the Fed can also adjust Reserve Requirements for banks. Along with that, the rate paid on these reserves, Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER). Another key bank rate that is mostly invisible to consumers is the Discount Rate. This is the interest rate at which banks can borrow money directly from the Federal Reserve. The discount rate is set by the Fed’s Board of Governors and is typically higher than the Federal Funds rate.

Banks try to avoid going to the Discount Window at the Fed because using this more expensive money is a sign to investors or depositors that something may be unhealthy at the institution. Figures for banks using this facility are reported each Thursday afternoon. There doesn’t seem to be bright flashing warning signs in the March 9 report. The amount lent on average for the seven-day period ending Thursday March 9, had decreased substantially, following a decrease the prior week. While use of the Discount Window facility is just one indicator of the overall banking systems health, it is not sending up red flags for the Fed or other stakeholders.

The European Central Bank Raised Rates

There is an expression, “when America sneezes, the world catches a cold.” The actions of the central bank in Europe, (the equivalent of the Federal Reserve in the U.S.) demonstrates that the bank failures in the U.S. are viewed as less than a sneeze. The ECB raised interest rates by half of a percentage point on Thursday (March 16). This is in line with its previously stated plan, even as the U.S. worries surrounding the banking system have shaken confidence in banks and the financial markets in recent days.

The ECB didn’t completely ignore the noise across the Atlantic; it said in a statement that its policymakers were “monitoring current market tensions closely” and the bank “stands ready to respond as necessary to preserve price stability and financial stability in the euro area.”

While Fed Chair Powell is restricted from making public addresses during the pre-FOMC blackout period, it is highly likely that there have been conversations with his cohorts in Frankfurt.

The Fed’s Upcoming Decision

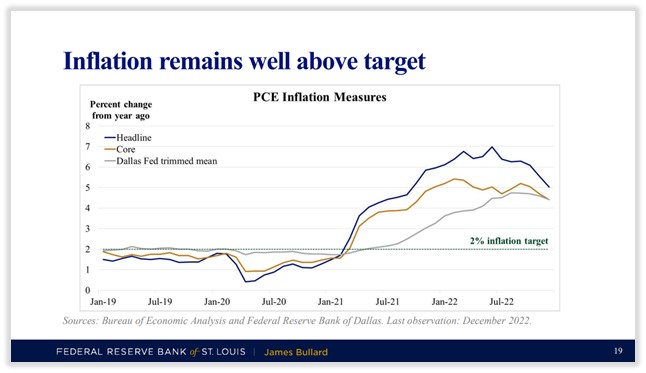

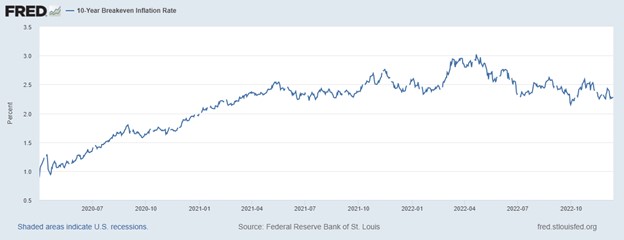

On March 14, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported core inflation (without volatile food and energy) rose in February. Another indicator, the most recent PCE index released on February 24 also demonstrated that core prices are rising at a pace faster than the Fed deems healthy for consumers, banking, or the economy at large. The inflation numbers suggest it would be perilous for the Fed to pause its tightening efforts now.

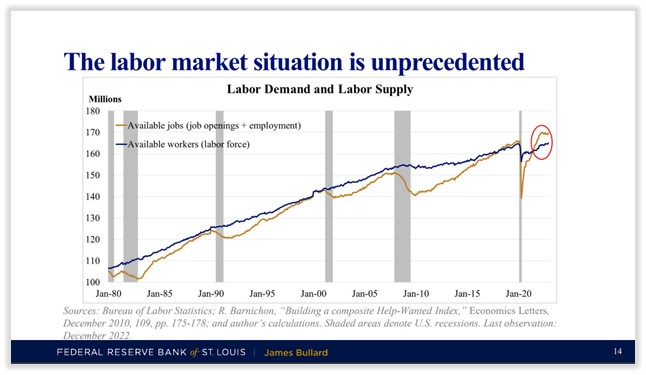

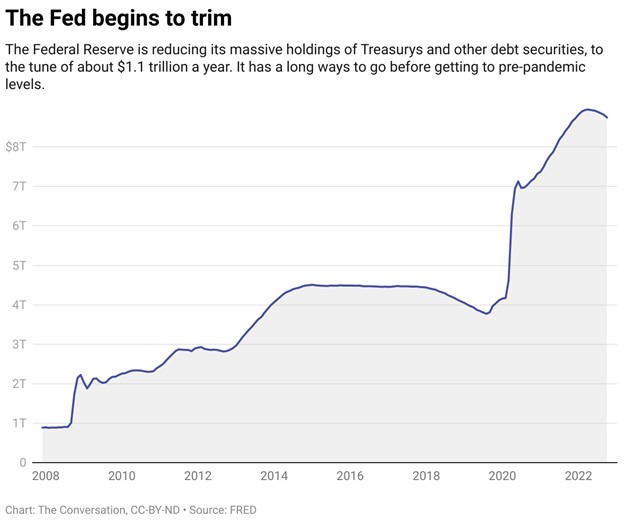

What has so far been limited to a few U.S. banks is not likely to have been a complete surprise to those that have been setting monetary policy for the last 12 months. It may have surprised most market participants, but warning signs are usually picked up by the FRS, FDIC, and even OCC well in advance. And before news of a bank closure becomes public. Yet, the FOMC continued raising rates and implementing quantitative tightening. The big difference today is, the world is now aware of the problems and the markets are spooked.

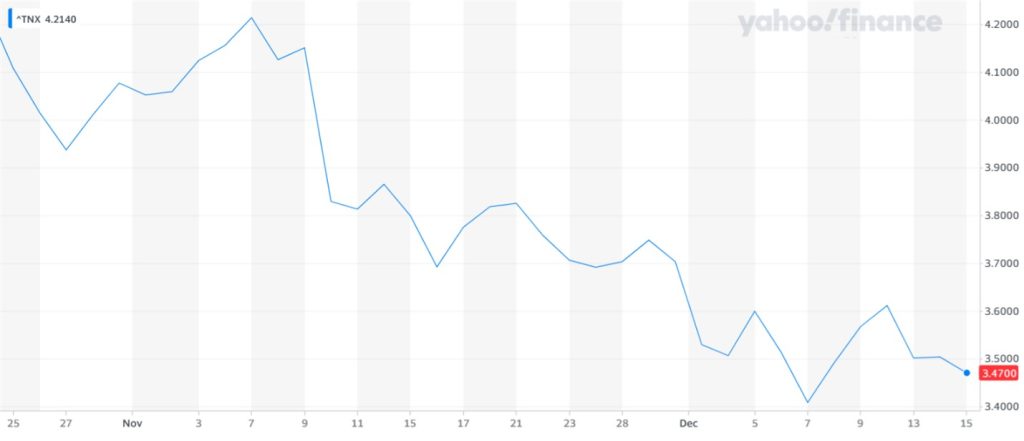

The post-meeting FOMC statement will likely differ vastly from the past few meetings. While what the Fed decides to do remains far from certain, what is certain is that inflation is still a problem, and rising interest rates mathematically erode the value of bank assets. At the same time, money supply (M2) is declining at its fastest rate in history. At its most basic definition, M2 is consumer’s cash position, including held at banks. As less cash is held at banks, some institutions may find themselves in the position SVB was in; they have to sell assets to meet withdrawals. The asset values, which were “purchased” at lower rates, now sell for far less than were paid for them.

This would seem to put the Fed in a box. However, if it uses the Discount Window tool, and makes borrowing easier by banks, it may be able to satisfy both demands. Tighter monetary policy, while providing liquidity to banks that are being squeezed.

Take Away

What the Fed will ultimately do remains far from certain. And a lot can happen in a week. Bank closings occur on Friday’s so the FDIC has the weekend to seize control. So if you’re concerned, don’t take Friday afternoons off.

If the Fed Declines to raise rates in March it could send a signal that the Fed is weakening its fight against inflation. This could cause rates to spike higher in anticipation of rising inflation. Everyone loses if that is the case, consumers, banks, and those holding U.S. dollars.

The weakness appears to be isolated in the regional-bank sector and was likely known to the Fed prior to the closing of the banks.

Consider this, only two things have changed for Powell since the last meeting, one is rising core CPI. The other is that he will have to do an even better job at building confidence post-FOMC meeting. Business people and investors want to know that the Fed can handle the hiccups along the path to stamping out high inflation.

Managing Editor, Channelchek

Sources