The Many Factors that Come Into a Fed Rate Decision are Mind Boggling

What do the FOMC members look at as they’re changing interest rates and whipping up new policy stances?

The Federal Open Market Committee, or FOMC, meets eight times a year. There are 12 members; seven are board members of the Federal Reserve System, and five are Reserve Bank presidents, including the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, who serves as president of the committee. The group, as a whole, is arguably among the most powerful entities in the world. What is it that this group, that impacts all of us, focus on? And what specifically will they weigh into their decision at the current meeting?

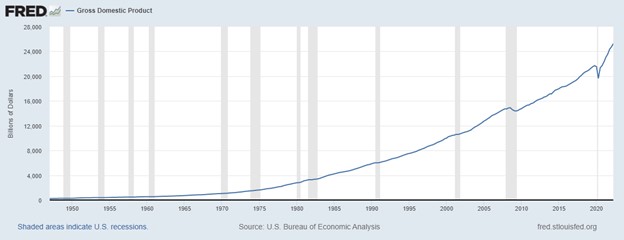

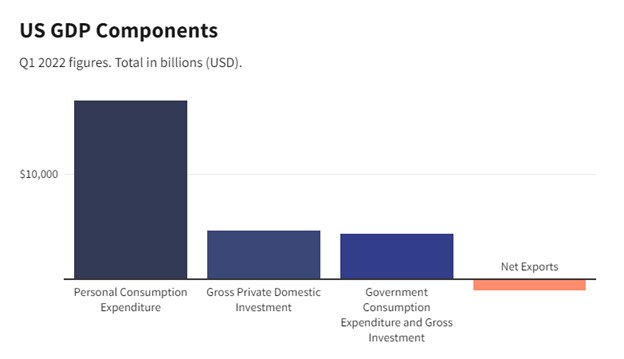

Labor markets and prices are top on the Fed’s list and specifically part of their mandate. Also feeding into the mandate are contributing factors like housing, growth trends, and risks to monetary policy.

Prices (Inflation Rates)

Inflation remains elevated. In September, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) picked up to 0.4%. Energy prices declined in each month of the third quarter, dropping a cumulative 11.3% since June. The Fed will have to discern if this is sustainable or a function of oil reserve releases that will need replacing. Food prices continued high, although at a slower 0.8% increase during September.

Core CPI inflation (which strips out energy and food) started the third quarter at a somewhat slow pace—increasing just 0.3% in July. The trend went against the Fed as it rose by 0.6% in both August and September. Price growth for services was the largest contributor to an increase in core CPI in the third quarter.

One of the two mandates of the Federal Reserve is to keep inflation at bay. Chairman Powell has said they are targeting a 2% annual inflation level. While nothing that has been reported in price increases since the last meeting has approached that low of a target, the Fed also has to consider their tightening moves do not work to lower demand (especially in food and energy) rapidly.

The Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation is the PCE price index; this is the measure they use with their 2% target. The PCE price index typically shows lower price growth than CPI because it uses a different methodology in its calculation, but the drivers of both measures remain similar. Over the year ending September, the headline PCE price index rose 6.2 percent, while the core PCE price index was up 5.1 percent.

Jobs (Employment and Wages)

Labor markets are still tight. The economy has added an additional 3.8 million jobs this year through September. This includes 1.1 million during the most recent quarter. During the third quarter, the U.S. economy exceeded pre-pandemic employment levels. The unemployment rate hasn’t budged much, and as of September, the rate held at a comfortable 3.5 percent rate.

The broadest measure of unemployment—the U-6 rate is a measure of labor underutilization that includes underemployment and discouraged workers, in addition to the unemployed. The U-6 rate has also remained behaved all year. It stood at 6.7 percent in September, the lowest rate in the history of the series (starting in January 1994).

When the Fed pushes on a lever for one of its mandates, in this case it is tightening to reign in inflation, it has to watch the impact on its other mandate, in this case, the job market. So far, there is nothing that has occurred on the employment side that should tell the Fed they have gone too far too fast.

.In fact, the labor numbers may suggest they should discuss whether they have moved nearly fast enough. Competition for employees continued as the economy added an additional 3.8 million through September 2022 (1.1 million during the third quarter). Notably, during the third quarter, the economy surpassed pre-pandemic employment levels as of August 2022.

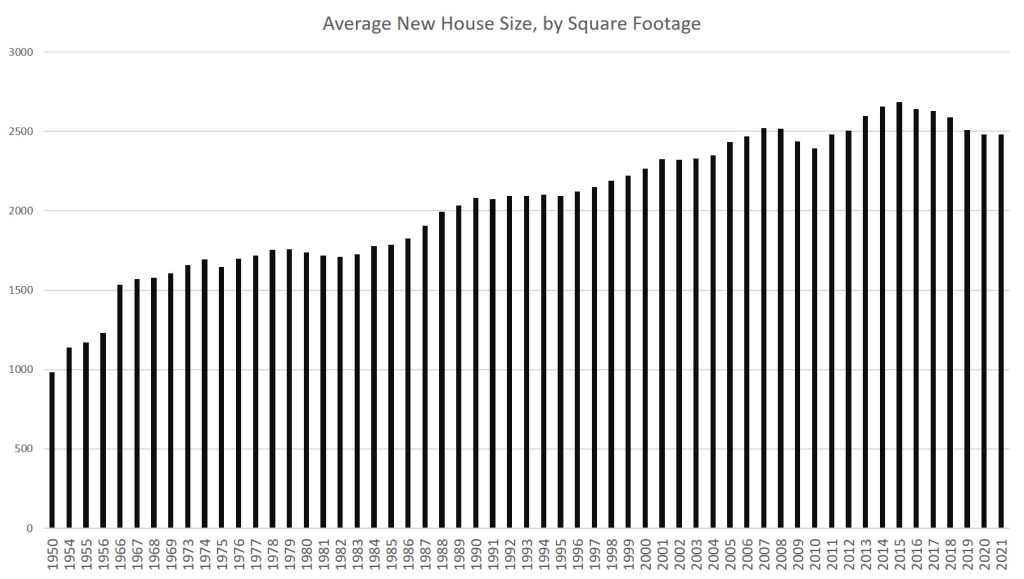

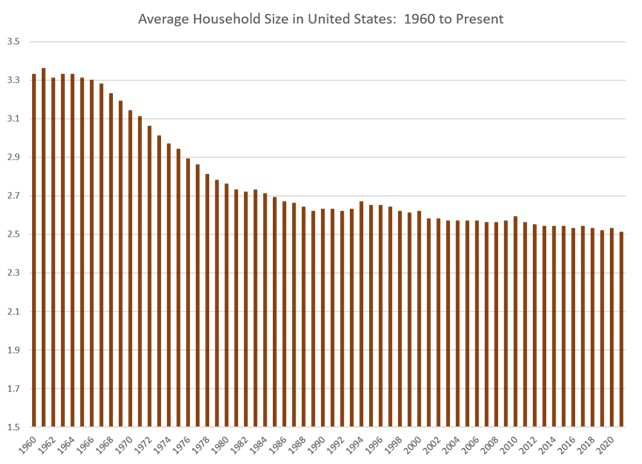

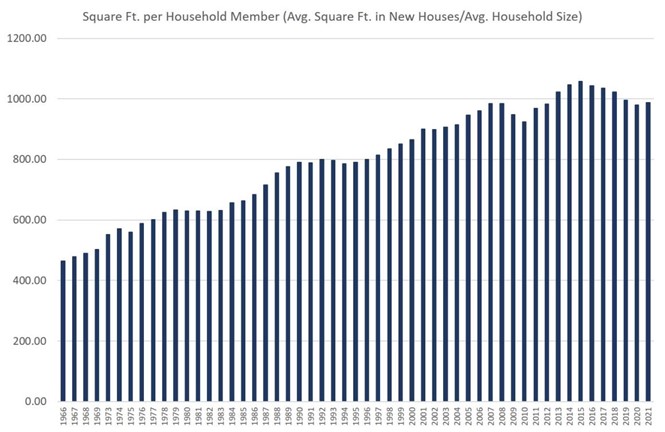

Housing Markets

Housing demand decreased in the third quarter as affordability (lending rates + prices), with economic uncertainty weighed on homebuyers. During September, 90% of all home sales were of existing homes. This pace declined 1.5 percent over the month (down 23.8 percent on a twelve-month basis). New single-family home sales dropped a large 10.9% in September; this was the seventh monthly decline.

Homes available for sale have now risen from all-time lows; this includes new and existing.

Over the past few years, home prices have increased dramatically; this was fueled by Fed policy. Prices still remain above longer-term trendlines. The Case-Shiller national house price index measures sales prices of existing homes; this was up 13% over the year ending August 2022. For reference, for the 12 months ended August 2021, prices rose 20%. The prior year they had only increased 5.8%.

Housing plays a huge role in economic health. The Fed is well aware of all the housing-related inputs to the 2008 financial crisis and the part easy money plays in market crashes. Orchestrating an orderly slowdown to the boom in housing is certainly critical to the Fed’s success.

Other Risks to Economy

Eight times a year, information related to each of the 12 Federal Reserve districts is gathered and bound in a publication known as theBeige Book. This summary of economic activity throughout the U.S. is provided approximately two weeks before each FOMC meeting, so members have a chance to evaluate economic activity over the diverse businesses the U.S. engages in.

U.S. Inflation can arise from conditions outside of the control of the U.S. For example Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has added upward pressure to inflation this year. This impact may have to be determined and netted out of calculations and policy as the Fed can’t fight this inflation pressure with monetary policy. An example would be the Fed can’t alter global food shortages brought on by war.

Dollar strength or weakness comes from many things. One of the most impactful is the difference in interest rates net of inflation between countries and their native currency. If the Fed raises rates when a competing currency has not, there is a chance there will be more demand for the alternative currency, which would weaken the dollar. Further complicating this for the Federal Resreve is a lower dollar is inflationary as it causes import prices to rise, a stronger dollar can reduce domestic economic activity as exports fall. The U.S. dollar has been rising and is now at its strongest in 20 years.

Commodity Prices were elevated in the first half of this year, mostly by energy. Although there was some relief from gas prices over the summer, energy is expected to rise into the colder months. They may rise further as the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserves are used less to control prices, this may be curtailed. The White House’s two goals of sharply reducing Russian revenue and avoiding further disruptions to global energy supplies while at the same time reducing oil use and production within the U.S. are a tanglement the Fed needs to consider. These can be very impactful to costs and economic activity, yet The Fed has no direct levers to impact these economic inputs.

World economies play a part in our own economic pace. If the Fed were to tighen aggressively while the global business is slowing, the impact of the tightening might be more pronounced than if the world economies are booming. Demand for goods and services impacts prices; the U.S. doesn’t live in a vacuum, and demand for our production and our demand for foreign production all must weigh on the Feds outlook for global economic health.

According to the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook, global growth is expected to slow to 3.2 percent in 2022 and just 2.7 percent in 2023. At the same time, central banks around the world are tightening monetary policy to fight high global rates of inflation. In addition, there has been financial instability in some major world economies. These rising risks to the global growth outlook may feed back into the U.S. outlook by weakening international demand for U.S. goods and service exports. On the positive economic side, China is considering easing its Zero-COVID policy, which could eventually ease the supply chain impact to inflation.

Take Away

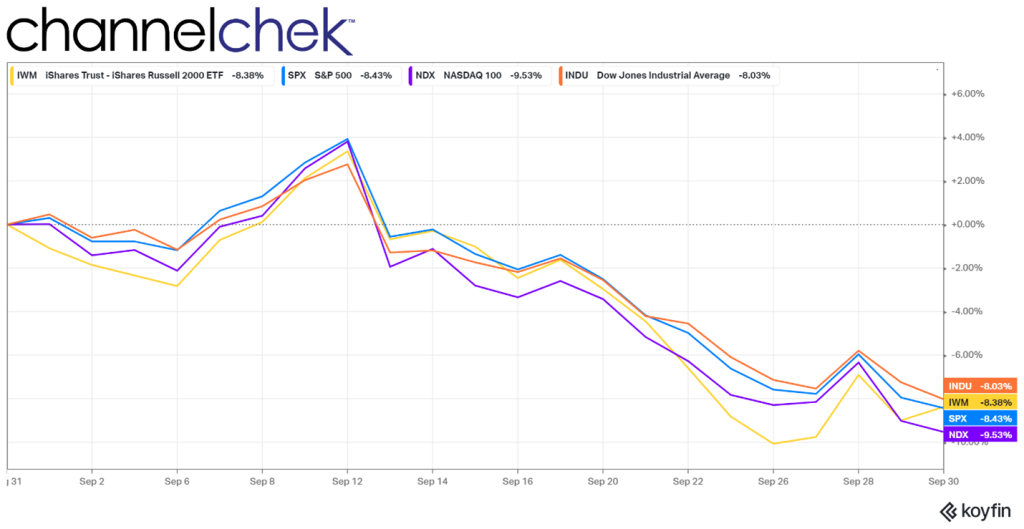

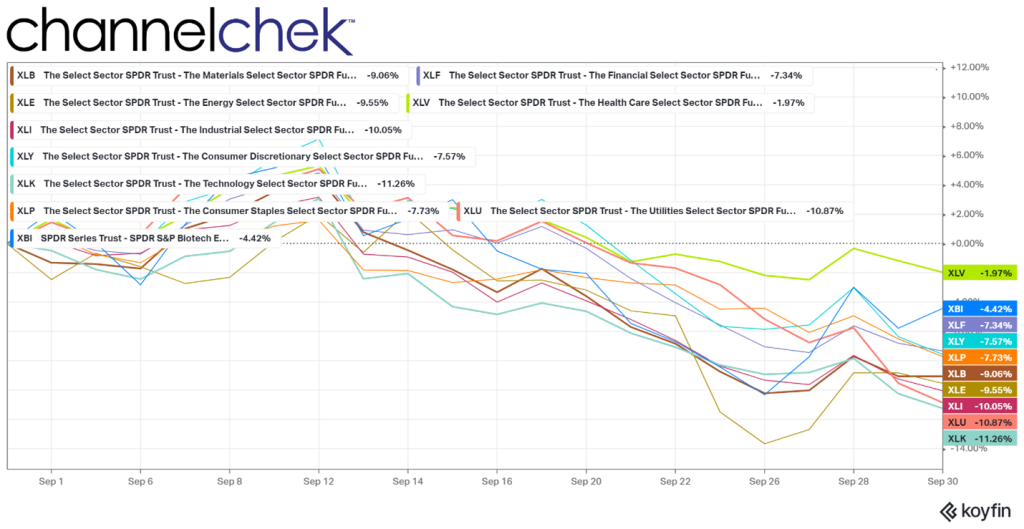

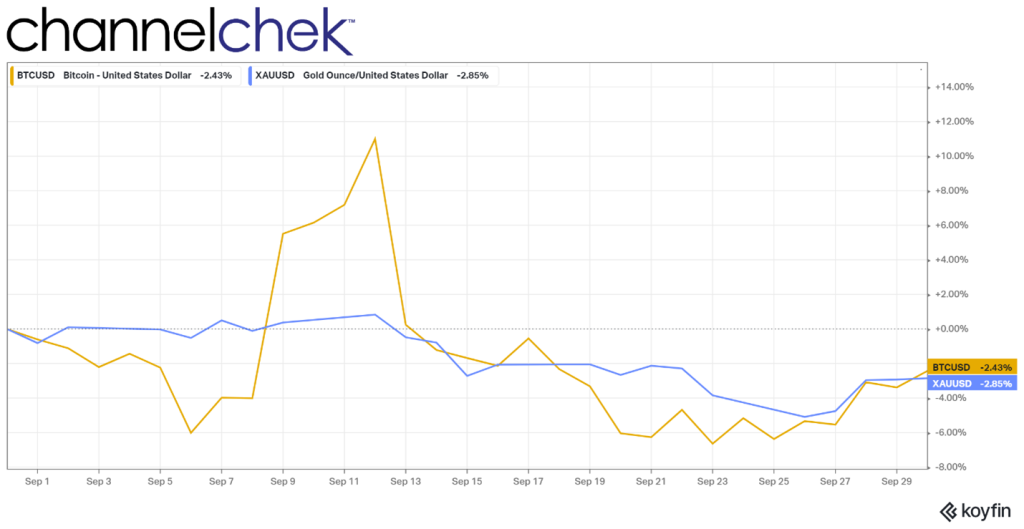

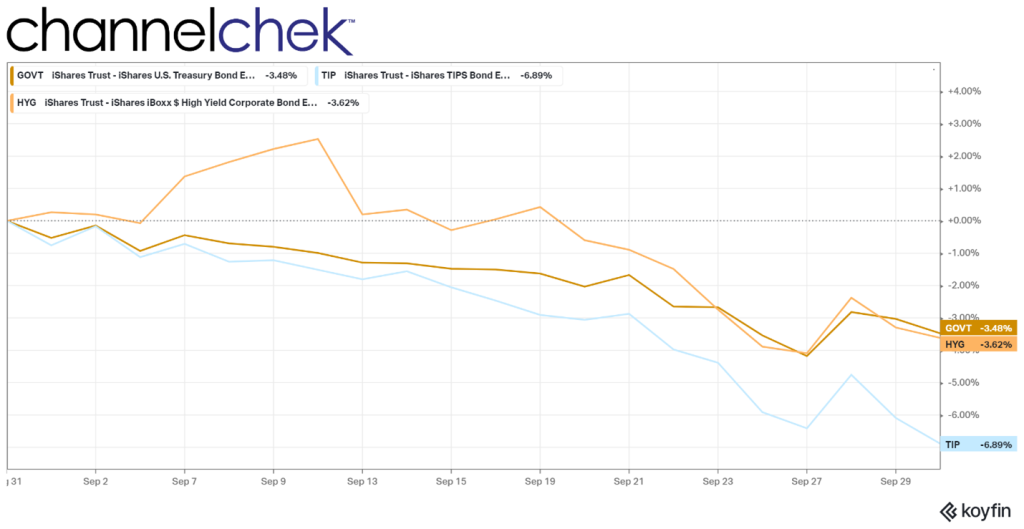

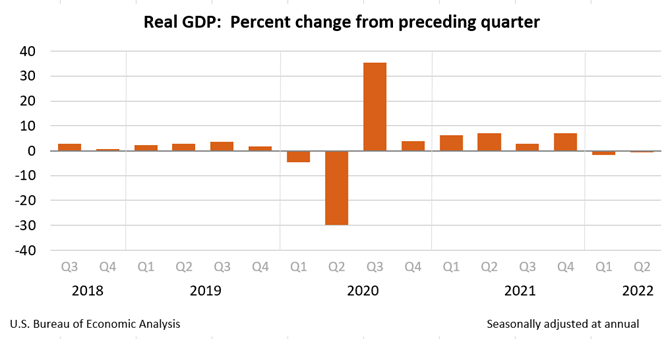

The original question was, “What do the FOMC members look at as they’re changing interest rates and whipping up new policy stances?” The answer is they have to look at everything. The recent mix of “everything” shows growth and employment in the U.S. have sustained at an even keel. Will previous rate hikes to calm inflation eventually take their toll? This is probably the big question the FOMC will be evaluating. Other domestic issues, including housing and the financial markets, are certainly to be weighed as well – a market crash of any magnitude could quickly slow economic activity.

The Fed has little control over what goes on overseas but must be aware of and hedge its policy to allow for.

All told, the Federal Reserve has a very difficult job. The report of the new monetary policy stance should hit the wire at 2 pm ET today (November 2).

Managing Editor, Channelchek

Sources