The Fed Is Losing Tens of Billions: How Are Individual Federal Reserve Banks Doing?

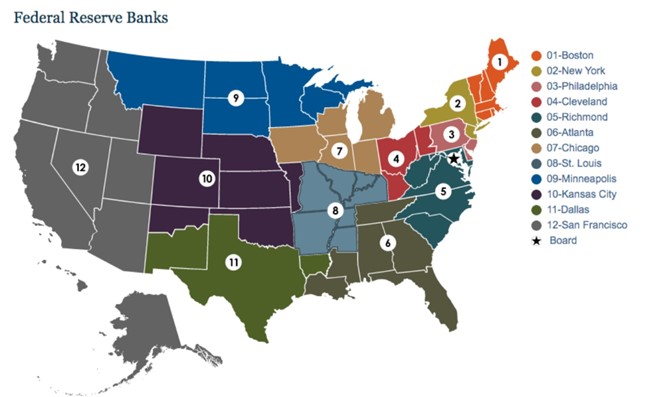

The Federal Reserve System as of the end of July 2023 has accumulated operating losses of $83 billion and, with proper, generally accepted accounting principles applied, its consolidated retained earnings are negative $76 billion, and its total capital negative $40 billion. But the System is made up of 12 individual Federal Reserve Banks (FRBs). Each is a separate corporation with its own shareholders, board of directors, management and financial statements. The commercial banks that are the shareholders of the Fed actually own shares in the particular FRB of which they are a member, and receive dividends from that FRB. As the System in total puts up shockingly bad numbers, the financial situations of the individual FRBs are seldom, if ever, mentioned. In this article we explore how the individual FRBs are doing.

All 12 FRBs have net accumulated operating losses, but the individual FRB losses range from huge in New York and really big in Richmond and Chicago to almost breakeven in Atlanta. Seven FRBs have accumulated losses of more than $1 billion. The accumulated losses of each FRB as of July 26, 2023 are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Accumulated Operating Losses of Individual Federal Reserve Banks

New York ($55.5 billion)

Richmond ($11.2 billion )

Chicago ( $6.6 billion )

San Francisco ( $2.6 billion )

Cleveland ( $2.5 billion )

Boston ( $1.6 billion )

Dallas ( $1.4 billion )

Philadelphia ($688 million)

Kansas City ($295 million )

Minneapolis ($151 million )

St. Louis ($109 million )

Atlanta ($ 13 million )

The FRBs are of very different sizes. The FRB of New York, for example, has total assets of about half of the entire Federal Reserve System. In other words, it is as big as the other 11 FRBs put together, by far first among equals. The smallest FRB, Minneapolis, has assets of less than 2% of New York. To adjust for the differences in size, Table 2 shows the accumulated losses as a percent of the total capital of each FRB, answering the question, “What percent of its capital has each FRB lost through July 2023?” There is wide variation among the FRBs. It can be seen that New York is also first, the booby prize, in this measure, while Chicago is a notable second, both having already lost more than three times their capital. Two additional FRBs have lost more than 100% of their capital, four others more than half their capital so far, and two nearly half. Two remain relatively untouched.

Table 2: Accumulated Losses as a Percent of Total Capital of Individual FRBs

New York 373%

Chicago 327%

Dallas 159%

Richmond 133%

Boston 87%

Kansas City 64%

Cleveland 56%

Minneapolis 56%

San Francisco 48%

Philadelphia 46%

St. Louis 11%

Atlanta 1%

Thanks to statutory formulas written by a Congress unable to imagine that the Federal Reserve could ever lose money, let alone lose massive amounts of money, the FRBs maintained only small amounts of retained earnings, only about 16% of their total capital. From the percentages in Table 2 compared to 16%, it may be readily observed that the losses have consumed far more than the retained earnings in all but two FRBs. The GAAP accounting principle to be applied is that operating losses are a subtraction from retained earnings. Unbelievably, the Federal Reserve claims that its losses are instead an intangible asset. But keeping books of the Federal Reserve properly, 10 of the FRBs now have negative retained earnings, so nothing left to pay out in dividends.

On orthodox principles, then, 10 of the 12 FRBs would not be paying dividends to their shareholders. But they continue to do so. Should they?

Much more striking than negative retained earnings is negative total capital. As stated above, properly accounted for, the Federal Reserve in the aggregate has negative capital of $40 billion as of July 2023. This capital deficit is growing at the rate of about $ 2 billion a week, or over $100 billion a year. The Fed urgently wants you to believe that its negative capital does not matter. Whether it does or what negative capital means to the credibility of a central bank can be debated, but the big negative number is there. It is unevenly divided among the individual FRBs, however.

With proper accounting, as is also apparent from Table 2, four of the FRBs already have negative total capital. Their negative capital in dollars shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Federal Reserve Banks with Negative Capital as of July 2023

New York ($40.7 billion)

Chicago ($ 4.6 billion )

Richmond ($ 2.8 billion )

Dallas ($514 million )

In these cases, we may even more pointedly ask: With negative capital, why are these banks paying dividends?

In six other FRBs, their already shrunken capital keeps on being depleted by continuing losses. At the current rate, they will have negative capital within a year, and in 2024 will face the same fundamental question.

What explains the notable differences among the various FRBs in the extent of their losses and the damage to their capital? The answer is the large difference in the advantage the various FRBs enjoy by issuing paper currency or dollar bills, formally called “Federal Reserve Notes.” Every dollar bill is issued by and is a liability of a particular FRB, and the FRBs differ widely in the proportion of their balance sheets funded by paper currency.

The zero-interest cost funding provided by Federal Reserve Notes reduces the need for interest-bearing funding. All FRBs are invested in billions of long-term fixed-rate bonds and mortgage securities yielding approximately 2%, while they all pay over 5% for their deposits and borrowed funds—a surefire formula for losing money. But they pay 5% on smaller amounts if they have more zero-cost paper money funding their bank. In general, more paper currency financing reduces an FRB’s operating loss, and a smaller proportion of Federal Reserve Notes in its balance sheet increases its loss. The wide range of Federal Reserve Notes as a percent of various FRBs’ total liabilities, a key factor in Atlanta’s small accumulated losses and New York’s huge ones, is shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Federal Reserve Notes Outstanding as a Percent of Total Liabilities

Atlanta 64%

St. Louis 60%

Minneapolis 58%

Dallas 51%

Kansas City 50%

Boston 45%

Philadelphia 44%

San Francisco 39%

Cleveland 38%

Chicago 26%

Richmond 23%

New York 17%

The Federal Reserve System was originally conceived not as a unitary central bank, but as 12 regional reserve banks. It has evolved a long way toward being a unitary organization since then, but there are still 12 different banks, with different balance sheets, different shareholders, different losses, and different depletion or exhaustion of their capital. Should it make a difference to a member bank shareholder which particular FRB it owns stock in? The authors of the Federal Reserve Act thought so.

About the Author

Alex J. Pollock is a Senior Fellow at the Mises Institute, and is the co-author of Surprised Again! — The Covid Crisis and the New Market Bubble (2022). Previously he served as the Principal Deputy Director of the Office of Financial Research in the U.S. Treasury Department (2019-2021), Distinguished Senior Fellow at the R Street Institute (2015-2019 and 2021), Resident Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (2004-2015), and President and CEO, Federal Home Loan Bank of Chicago (1991-2004). He is the author of Finance and Philosophy—Why We’re Always Surprised (2018).