As March Madness Looms, Growth in Legalized Sports Betting May Pose a Threat to College Athletes

March Madness began on March 14, 2023, it’s a sure bet that millions of Americans will be making wagers on the annual college basketball tournament.

The American Gaming Association estimates that in 2022, 45 million people – or more than 17% of American adults – planned to wager US$3.1 billion on the NCAA tournament. That makes it one of the nation’s most popular sports betting events, alongside contests such as the Kentucky Derby and the Super Bowl. By at least one estimate, March Madness is the most popular betting target of all.

While people have been betting on March Madness for years, one difference now is that betting on college sports is legal in many states. This is largely due to a 2018 Supreme Court ruling that cleared the way for each state to decide whether to permit people to gamble on sporting events. Prior to the ruling, legal sports betting was only allowed in Nevada.

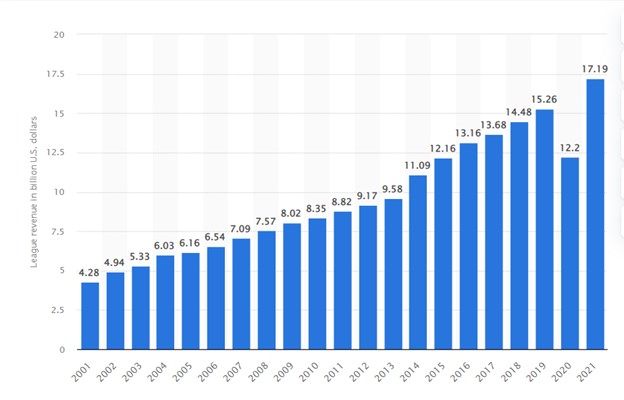

Since the ruling, sports betting has grown dramatically. Currently, 36 states allow some form of legalized sports betting. And now, Georgia, Maine and Kentucky are proposing legislation to make sports betting legal.

About two weeks after sports betting became legal in Ohio on Jan. 1, 2023, someone, disappointed by an unexpected loss of the University of Dayton men’s basketball team to Virginia Commonwealth University, made threats and left disparaging messages against Dayton athletes and the coaching staff.

The Ohio case is by no means isolated. In 2019, a Babson College student who was a “prolific sports gambler” was sentenced to 18 months in prison for sending death threats to at least 45 professional and collegiate athletes in 2017.

Faculty members of Miami University’s Institute for Responsible Gaming, Lottery, and Sports are concerned that the increasing prevalence of sports betting could potentially lead to more such incidents, putting more athletes in danger of threats from disgruntled gamblers who blame them for their gambling losses.

The anticipated growth in sports gambling is quite sizable. Analysts estimate the market in the U.S. may reach over US$167 billion by 2029.

Gambling Makes Inroads into Colleges

Concerns over college athletes being targeted by upset gamblers are not new. Players and sports organizations have expressed worry that expanded gambling could lead to harassment and compromise their safety. Such concerns led the nation’s major sports organizations – MLB, NBA, NFL, NHL and NCAA – to sue New Jersey in 2012 over a plan to initiate legal sports betting in that state. They argued that sports betting would make the public think that games were being thrown. Ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled that it was up to states to decide if they wanted to permit legal gambling.

Sports betting has also made inroads into America’s college campuses. Some universities, such as Louisiana State University and Michigan State University, have signed multimillion-dollar deals with casinos or gaming companies to promote gambling on campus.

Athletic conferences are also cashing in on the data related to these games and events. For instance, the Mid-Atlantic Conference signed a lucrative five-year deal in 2022 to provide real-time statistical event data to gambling companies, which then leverage the data to create real-time wager opportunities during sporting events.

As sports betting comes to colleges and universities, it means the schools will inevitably have to deal with some of the negative aspects of gambling. This potentially includes more than just gambling addiction. It could also involve the potential for student-athletes and coaches to become targets of threats, intimidation or bribes to influence the outcome of events.

The risk for addiction on campus is real. According to the National Council on Problem Gambling, over 2 million adults in the U.S. have a “serious” gambling problem, and another 4 million to 6 million may have mild to moderate problems. One report estimates that 6% of college students have a serious gambling problem.

What Can be Done?

Two faculty fellows at Miami University’s Institute for Responsible Gaming, Lottery, and Sport – former Ohio State Senator William Coley and Sharon Custer – recommend that regulators and policymakers work with colleges and universities to reduce the potential harm from the growth in legal gaming. Specifically, they recommend that each state regulatory authority:

- Develop plans to coordinate between different governmental agencies to ensure that individuals found guilty of violations are sanctioned in other jurisdictions.

- Dedicate some of the revenue from gaming to develop educational materials and support services for athletes and those around them.

- Create anonymous tip lines to report threats, intimidation or influence, and fund an independent entity to respond to these reports.

- Assess and protect athlete privacy. For instance, schools might decline to publish contact information for student-athletes and coaches in public directories.

- Train athletes and those around them on basic privacy management. For instance, schools might advise athletes to not post on public social media outlets, especially if the post gives away their physical location.

The NCAA or athletic conferences could lead the development of resources, policies and sanctions that serve to educate, protect and support student-athletes and others around them who work at the schools for which they play. This will require significant investment to be comprehensive and effective.

This article was republished with permission from The Conversation, a news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It represents the research-based findings and thoughts of, Jason W. Osborne, Professor of Statistics, Institute for Responsible Gaming, Lottery, and Sport, Miami University.