The Reasons Biotech is Gaining Ground on the Field

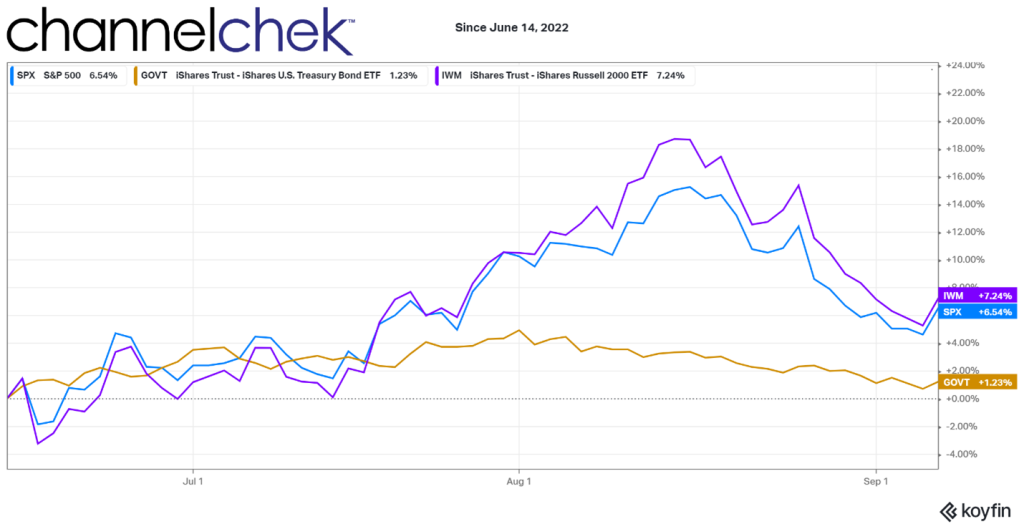

Similar to their watching a horse race, with a sense that their horse is starting to come from behind and may even be moving toward the front of the pack, biotech investors are leaning over the rail, watching their sector’s increased pace. This week biotechs, as measured by the ETF $XBI, crossed above its 200-day moving average – only last week the biotech sector’s momentum took it above its 50-day moving average. Does this technical indicator demonstrate the growing strength will continue, or does this indicate that it may be approaching overbought?

Technical analysis is not usually clear on this; below, we look for clues in the sector’s fundamentals to better handicap its chances.

Pace of Deals

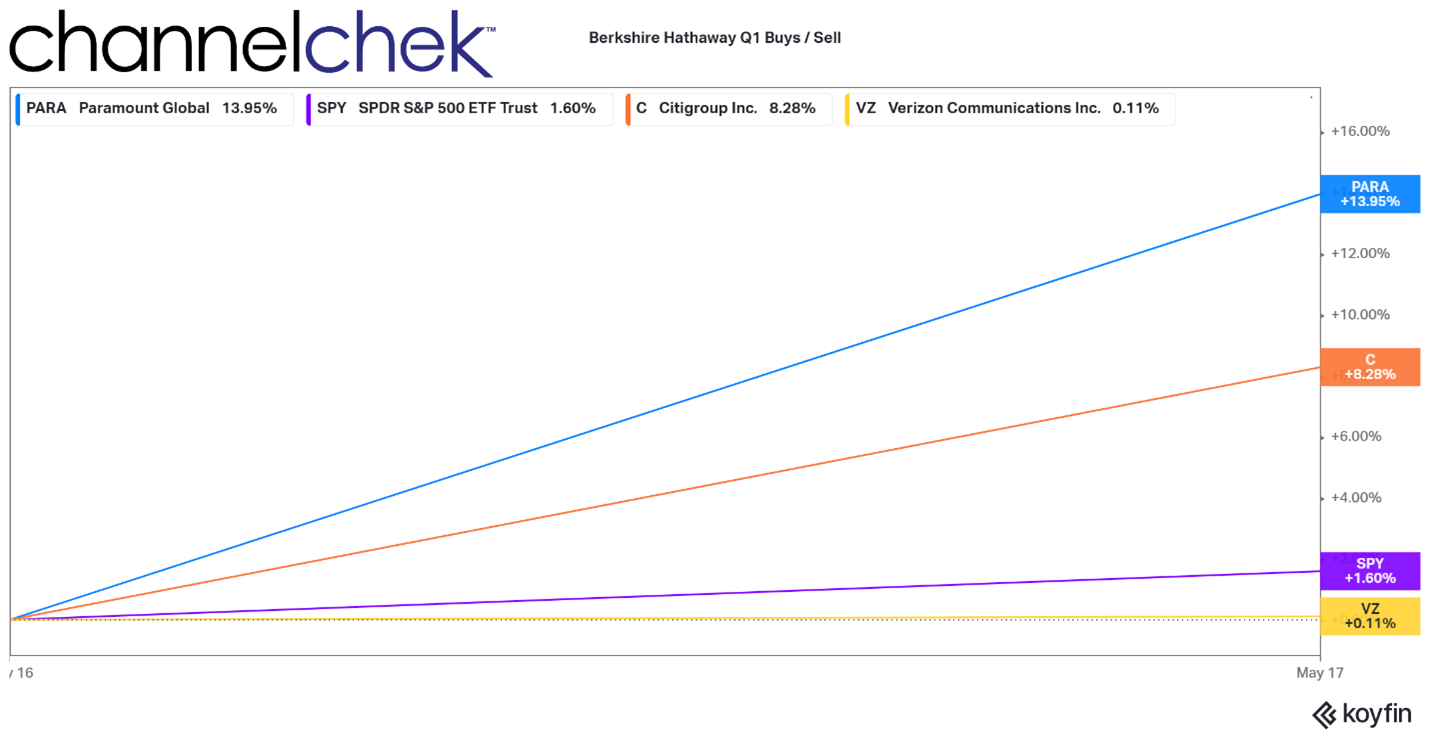

In 2021, the overall healthcare sector experienced record merger and acquisition activity. The first half of 2022 also had significant activity; however, at $92.4 billion in value and 481 deals announced, the pace of activity was down 51% from the same period in 2021. This may feel slow but is well ahead of the pre-pandemic pace for these companies. For example, it’s a 37% increase from the first half of 2020. This could be seen as fundamentally positive for a sector that is trading below its 2021 levels and even below the second half of 2020.

One catalyst for this continued high pace of deals which may even help accelerate it, is that big pharmacies are flush with cash. This cash serves them best if invested in the next generation of medicine or valuable patent. Fortunately for big pharma, small and mid-sized biotech companies are more likely now to form financial partnerships, agree to merger arrangements, or be outright purchased in order to help with their need for cash to continue operations.

This dynamic is easy to understand; there is less money flowing into the smaller incubator-type companies than the big pharmaceutical companies that have had money pouring in from generous pandemic-related government contracts. These small companies, many working on what may be life-changing science, rarely have sizeable sales. Sales and revenue come after the final phase of testing, FDA approval, and marketing. A small biotech company that sees its research and development possibly making a difference a few years from now, but is currently burning through capital at a pace where it may only last another 12 months, might welcome partnership or acquisition talks with a cash-rich suitor.

News of any injection of cash or capital in these smaller biotechs is usually an event that pushes the price up by percentage points in a short period of time. A full buyout can do much more.

| XBI provides exposure to US biotech stocks, as defined by GICS, from a universe that invests across the market-cap spectrum. The fund equal-weights its portfolio, which in turn emphasizes small- and micro-caps and greatly reduces single-name risk. Thus, the weighted-average market-cap is much smaller than some competitors. Unlike other funds in this segment, XBI is a pure biotech play, with relatively small pharma overlap. The index is rebalanced quarterly. – FactSet |

Put yourself in the position of big pharma in 2022 into 2023. Your firm may now be sitting on a huge war chest thanks to the pandemic. This is now being eroded by high inflation. Management’s role is to use resources to provide value to shareholders. In the meantime, biotech is well-priced and motivated to talk.

And then the clock is always ticking on patent cliffs for big pharma. They may be very amenable to shop for acquisition targets as they look out at the expiration of patent rights and the exclusive protection those patents provide. Analysts estimate the top-ten pharmaceutical manufacturers have more than 46 percent of their revenues at risk between 2022 and 2030. Behemoths like Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer and Merck will be among the most exposed over the next decade.

Take Away

Watching a thoroughbred that was lagging behind the pack find an opening and begin to gain ground on those around it is exciting. When you have money on the horse, it’s even more enjoyable. The performance of the biotech sector was far behind other industries for much of this year. Moving into fall it has been outperforming its own average and many other investment areas.

There are fundamentals in play that could keep this strength going. What’s more is that these factors have little to do with the overall market, which many now fear

This challenge may catalyze M&A in the industry as large firms look to recoup lost revenue streams and invest in patents.

Managing Editor, Channelchek

Sources

https://www.nasdaq.com/articles/consolidation-case-for-biotech-etf-bbh

https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/big-pharma-firms-return-to-the-deal-6580128/