A Social Security Funded Study Demonstrates the Benefit of Including Equities

Should all or part of Social Security be invested in the stock market? A study out this month by the Center of Retirement Research (CRR) at Boston College uses evidence from the U.S. and Canada that shows that investing in equities through government retirement funds is feasible, safe, and effective. In 1984, before he became the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan headed a commission on Social Security (S.S.). While he was positive on stocks used for a portion of S.S., it was not part of the commission’s recommendation. Since then, equity returns have averaged about twice that of S.S. investments in U.S. Treasuries.

According to CRR, “evidence from the U.S. and Canada shows that such investing through government retirement funds is feasible, safe, and effective.”

The Center for Retirement Research is a non-profit research institute that studies retirement income security. It was established in 1998 as part of the Retirement Research Consortium and is funded by the U.S. Social Security Administration. The CRR’s mission is to produce first-class research and educational tools and forge a strong link between the academic community and decision-makers in the public and private sectors. The CRR conducts a wide variety of research projects on topics such as Social Security, private pensions, annuities, and retirement savings. It also publishes a variety of research reports, data sets, and educational materials. Policymakers, academics, and the media widely cite the CRR’s research.

Background

The merits of investing a portion of the Social Security trust fund in equities have been discussed for decades. With potentially higher returns compared to safer assets, such as Treasury bonds, equity investments could potentially reduce the need for tax increases or benefit cuts to ensure the long-term solvency of the system. However, this approach also carries risks and raises concerns about government interference in private markets and misleading accounting practices that may give the impression that issuing bonds and buying equities can effortlessly generate wealth for the government.

There are real-world examples that one can point to that demonstrate that governments can engage in equity investments sensibly. Canada, for instance, has a large, actively managed fund that adheres to fiduciary standards and employs conservative return assumptions. In the United States, both the Railroad Retirement System and the Federal Thrift Savings Plan have invested in a diverse range of assets without disrupting private markets. In these cases, the government’s role is primarily passive.

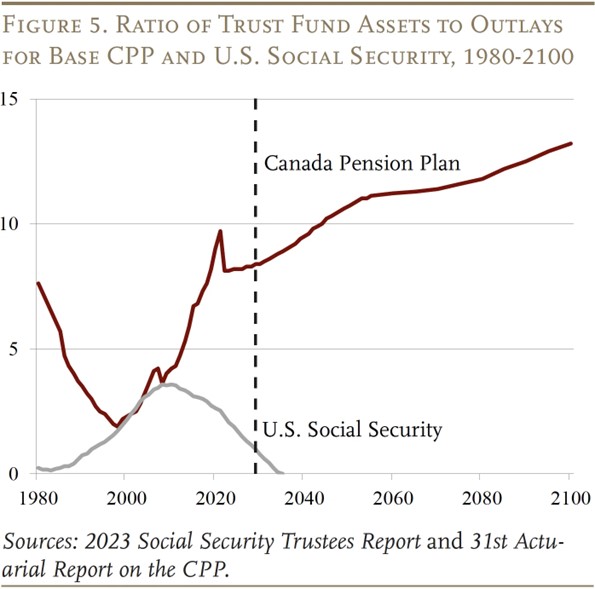

Despite the demonstrated successes, the question remains whether equity investments should be considered as a solution for Social Security. The prerequisite for such an approach is a trust fund with substantial assets available for investment. Currently, the existing trust fund is being depleted, and the likelihood of raising taxes to rebuild it is low. Borrowing to rebuild the trust fund does not guarantee any additional resources for Social Security.

After the Greenspan amendments in 1983, which resolved the problem for a time with taxing S.S., future deficits began to reappear. President Clinton tasked the 1994-1996 Advisory Council on Social Security with considering options for achieving long-term solvency. The council could not reach a consensus on a single plan, and its members put forward three different proposals to close the funding gap, all of which included some form of equity investment. Two proposals involved individual accounts for equity investment, while the third recommended direct equity investment using a portion of the trust fund reserves.

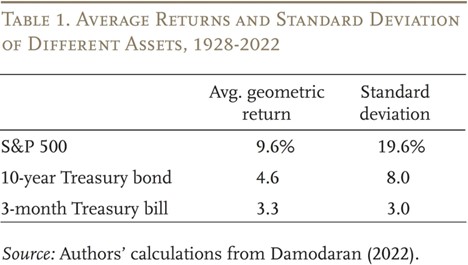

The primary attraction of equity investment lies in its higher expected rate of return compared to safer assets like Treasury bonds or bills. By restoring balance to Social Security, the need for tax increases or benefit cuts could be reduced (see Table 1). Economists also argue that effective risk-sharing across a lifespan requires individuals to bear more financial risk when young and less when old. As young individuals possess limited financial assets, investing the trust fund in equities becomes a means to achieve this goal.

Critics expressed concerns that equity investment by Social Security could have adverse effects on the stock market and corporate decision-making while also creating the false perception that trading bonds for stocks yields magical money.

Addressing these concerns involves answering the following questions:

How significant is the equity investment initiative relative to the overall economy? According to a 2016 study, if Social Security had begun investing in the stock market in 1984 or 1997, it would now own approximately 4 percent of the market. For comparison, state and local pension plans currently hold about 5 percent of total equities.

How do government officials select investments? Proponents of equity investment for the trust fund assume that the government would take a passive role. However, the Canada Pension Plan and the Railroad Retirement system, as discussed later, adopt a more active approach.

Do government agencies use expected returns or risk-adjusted returns to evaluate the impact of equities on plan finances? Crediting expected returns quantifies the potential contribution of equities to addressing Social Security’s financing shortfall but may falsely suggest that the government can generate money simply by selling bonds and buying stocks. Adjusting for risk avoids this misperception by acknowledging that returns are not guaranteed, but the risk adjustment would yield no immediate impact from equity investment on the system’s finances. Higher returns are only recognized after they are realized.

Three Federal Government Plans with Equity Investments

The Canada Pension Plan is a major component of Canada’s retirement system, initially established in 1966 as a pay-as-you-go plan with a modest reserve, similar to the U.S. Social Security program. This approach was suitable when the country had a young population and rapidly growing wages. However, factors such as declining birth rates, longer life expectancies, and lower real wage growth led to increased plan costs and the prospect of rising payroll contribution rates.

To address intergenerational fairness and ensure the long-term financial sustainability of the plan, Canada enacted legislation in 1997. The legislation increased payroll contributions to projected long-term rates and introduced equity investments into the fund. Any future changes to the plan must be fully funded.

The investment strategy was implemented through the creation of the CPP Investment Board (CPPIB), a government-owned corporation that operates independently from the CPP itself and is managed at arm’s length from the government. The CPPIB’s mandate is to invest excess CPP revenues in a way that maximizes returns without incurring undue risk, solely for the benefit of CPP contributors and beneficiaries.

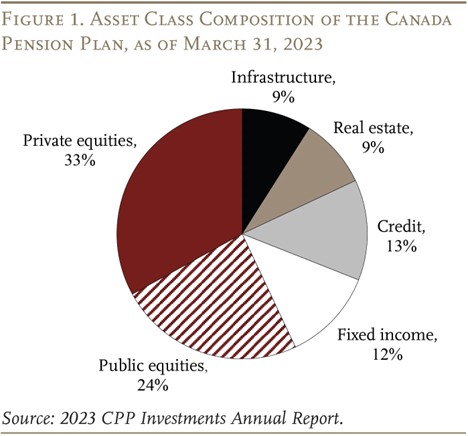

The CPPIB has built a diverse portfolio comprising stocks, bonds, real estate, infrastructure projects, and private equity (see Figure 1). As of 2023, the total assets amount to 570 billion CAD.

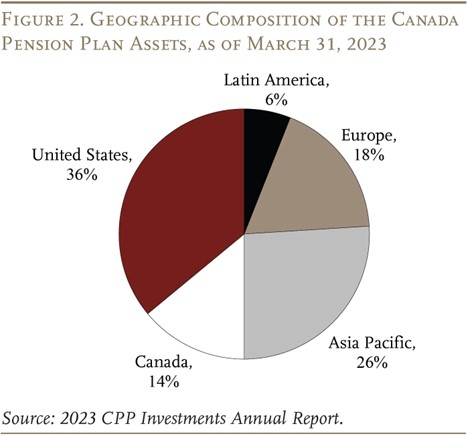

To reduce risks associated with future Canadian economic and demographic conditions, the CPPIB diversifies its investments globally (see Figure 2). Therefore, the fund’s domestic investments are relatively small compared to the country’s GDP (2.8 trillion CAD) and stock market (3.9 trillion CAD).

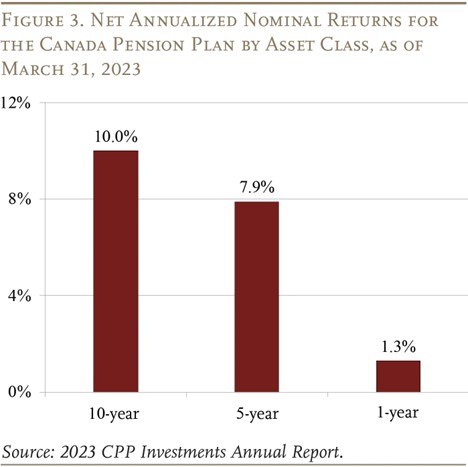

The CPPIB comprises six departments responsible for investing and managing the assets, employing highly compensated in-house managers. Over the past decade, the fund has achieved an annualized net return of 10 percent (see Figure 3).

The CPPIB also considers economic, social, and governance factors in its investment decisions when managers believe that addressing these issues will generate superior long-term returns. The Board exercises proxy voting at annual meetings and encourages companies to consider climate risks and develop viable transition strategies. Rather than engaging in blanket divestment from high-emitting sectors, the managers believe in using the CPPIB’s influence constructively.

The Board assesses risk using a minimum and a target level. The base CPP’s minimum risk level consists of a portfolio divided equally between Canadian government bonds and global public equities. In 2016, legislation was passed that increased CPP contributions and benefits. The minimum risk levels for the additional component are slightly lower: 60 percent bonds and 40 percent global equities.

The actuarial reports adopt conservative return assumptions, as the actual investment earnings have consistently exceeded projected earnings. Under these prudent assumptions, both the base CPP and the additional CPP components have been projected to remain sustainable for a 75-year period. If the system’s finances are projected to be imbalanced, an additional safeguard triggers an increase in contribution rates and a freeze in benefit indexation if policymakers fail to address the projected imbalance.

The Canadian investment initiative has proven successful while addressing the concerns raised by critics. Investments represent a small share of the Canadian economy, adhere to strict fiduciary standards, and the assumed investment returns used for evaluating the solvency of the CPP are conservative.

U.S. Railroad Retirement System

The Railroad Retirement system was created by Congress in 1934 to assume responsibility for the rail industry’s ailing pension plan. Initially funded on a pay-as-you-go basis through payroll taxes on workers and employers, the program had a modest trust fund invested solely in government bonds. However, by the 1990s, the trust fund’s assets had grown to four times the annual outlays, reaching historically high levels. There was a belief that further growth could be achieved through equity investments, leading management and labor to negotiate a proposal for such investments. However, given that Railroad Retirement is a government program, the plan required congressional approval.

Congress expressed concerns about potential political influence on investment decisions. To address this, Congress established the National Retirement Investment Trust (NRRIT). The NRRIT comprises six trustees, with three selected by management and three by labor, who then choose a seventh independent trustee. Congress also imposed a private-sector fiduciary mandate on these trustees, requiring them to invest the government’s assets solely in the interest of plan participants. Initially, 65 percent of trust fund assets were allocated to equities. Over time, the NRRIT expanded its portfolio beyond equities to include real estate, private equity, and private debt. As of 2023, the net assets in the trust fund amounted to $27 billion. External managers handle the actual investing.

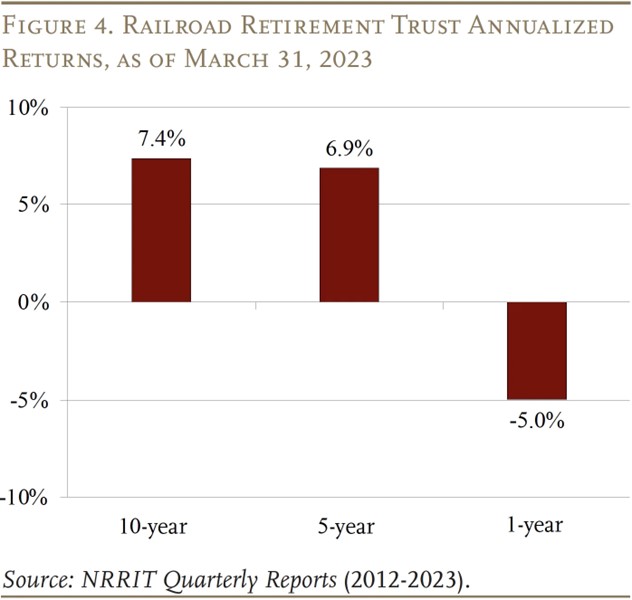

The evaluation of equity use in reform proposals raised a key issue. While the Social Security actuaries credit equities with their expected rate of return, the Office of Management and Budget, in assessing the financial implications of the Railroad Retirement proposal, disregarded the higher expected return and employed a risk-adjusted return—the long-term Treasury rate—to project future trust fund balances. Currently, the Railroad Retirement actuaries assume a 6.5-percent return, striking a balance between actual returns and a risk-adjusted rate.

Federal Thrift Savings Plan

Established in 1986, the Federal Thrift Savings Plan (TSP) boasts 6.5 million participants and approximately $800 billion in assets. Concerns among members of Congress regarding potential executive branch pressure on plan fiduciaries to select investment options that align with its policy goals prompted the establishment of stringent safeguards.

The Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board, responsible for administering the TSP, has limited discretion compared to other plan fiduciaries when setting investment policy. Congress determines the number and types of investment funds that the Board can offer, and any expansion or change requires congressional approval. When choosing benchmark indices for the investment funds, the Board is restricted to those that are widely recognized and reasonably represent the entire market. The Board is also prohibited from removing any stock from the index and categorically barred from using proxy voting power to influence corporate decision-making.

Francis Cavanaugh, the first executive director of the TSP’s Board, reported no difficulties in selecting an index or obtaining competitive bids from large index fund managers. He encountered no instances of government interference in the market. In essence, the TSP provides a model for structuring Social Security’s equity investment, with a passive approach through index funds and no proxy voting.

Does Equity Investments Make Sense in 2023?

In theory, the answer is “yes.” Plans that have adopted equity investments have consistently outperformed bond yields, even in the face of economic downturns such as the dot-com recession and the financial crisis. Concerning critics’ concerns, the experience of the TSP offers guidance on separating government intervention from actual investment decisions. Additionally, evaluating returns on a somewhat risk-adjusted basis, similar to the approach employed by the Railroad Retirement system, prevents the perception of easy money.

However, investing trust fund assets in equities necessitates a substantial trust fund. Unfortunately, the Social Security trust fund that emerged from the 1983 amendments is rapidly diminishing. Rebuilding the trust fund would require a tax increase to cover current program costs and generate an annual surplus to accumulate reserves.

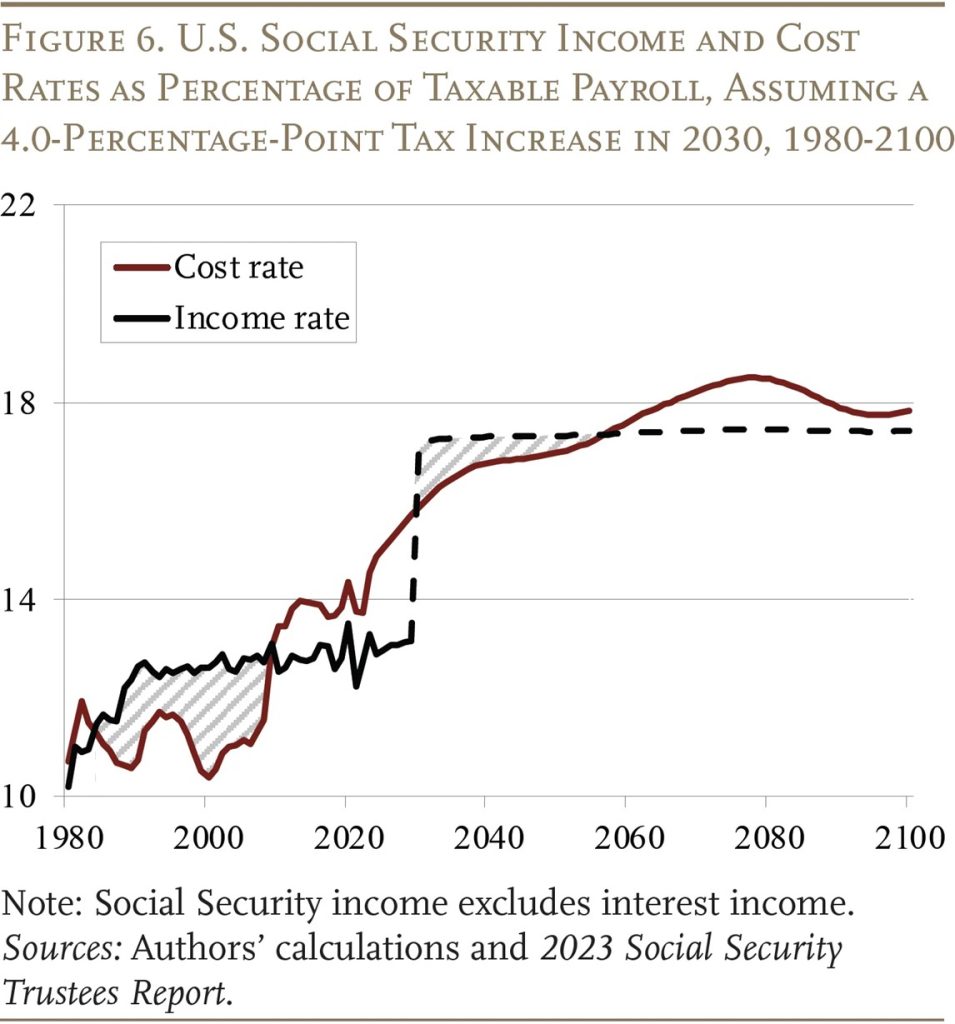

Although such an initiative is not without precedent—the United States and Canada both raised payroll contributions above current program costs and accumulated fund assets—present circumstances differ significantly from those in 1983. The majority of cost increases lie in the past. Even if Congress were to raise the payroll tax rate by 4 percentage points starting in 2030—an amount roughly needed to cover benefits over the next 75 years—it would only result in minor temporary surpluses, followed by future cash-flow deficits. These surpluses would be less than 40 percent of those generated by the 1983 legislation

Considering the unlikelihood of Congress taking action well before 2030, the combination of current trust fund balances and immediate surpluses resulting from the tax increase would only lead to modest accumulation.

Furthermore, it is questionable whether there is enough political will to implement such measures, and the case for building a large trust fund is not particularly compelling. With costs projected to stabilize, it is challenging to argue that today’s workers should pay more to build a trust fund that will benefit future workers.

If Congress is unwilling to raise taxes sufficiently to create a substantial trust fund, could borrowing be a viable solution? One proposal suggests that the government borrow around $1.5 trillion to invest in stocks, private equity, and other instruments with higher expected returns than government debt interest. In the interim, the government would continue borrowing to cover Social Security’s shortfall. After 75 years, the trust fund proceeds could be used to repay the borrowed funds that financed benefit payments.

This proposal differs fundamentally from Canada’s approach, which involves contributing additional funds to build up a reserve for the future. On the contrary, creating a trust fund with borrowed money that the government must repay with interest means that any proceeds would be limited to returns exceeding the bond rate. Fixing Social Security requires genuine economic changes, such as benefit reductions or increased income. This proposal offers no real solutions except the opportunity to pocket returns exceeding the bond rate.

Critics liken this proposal to advising a middle-aged couple who realize they have insufficient retirement savings to not reduce their spending, plan for reduced expenses after retirement,

Take Away

The US Social Security System investing in equities through retirement program trust funds is a viable concept that has been proven feasible, safe, and effective in both Canada and the United States. So, in theory, this idea could have worked, but can it may be late to attempt now. This is because one critical component is now deficient. SS no longer has a sizable trust fund to invest. And rebuilding the trust fund through additional taxes or borrowing may not be feasible.

While the mechanics are manageable, the window may have passed for raising taxes enough to accumulate a meaningful Social Security trust fund that would make investing in equities worthwhile and prudent according to the CRR.

Managing Editor, Channelchek

Sources

https://401kspecialistmag.com/do-equity-investments-make-sense-in-social-security/