|

|

|

|

Deciding on the Best Course for when the Storm Clears

Investors must be able to trust the aids on which they rely when navigating financial markets. If they can’t, they’re putting a lot at risk, themselves, and all who are depending on the performance of the assets. When market squalls arise, there must be confidence in decision methods and surety in your own ability to carry them out. A feeling of being way off course, for some, can cause clouded decisions and perhaps lead to the wrong actions. Complete confidence in where you are and how to proceed is required. To act or even not to act is a decision. Market storms cause us to lose trust in our strategies and question ourselves. People often freeze, some just start panic buying or selling. If you feel your methods and aids for navigating the market have taken you far off course, it’s hard to trust them. But, without having something to rely on, deciding what to do next is a shot in the dark.

There is nothing in this educational piece about deadly viruses, quarantines, or business closures. That’s intentional. The suggestions you’ll find as you scroll down are things I’ve learned over three-plus decades of all types of market storms. There is no need to point to a specific disruption; because there is one thing that is constant through all of them, human behavior. I will, however, warn you that the next section may be uncomfortable for some. Uncomfortable because it has you looking a bit into your reaction to adverse events. We’ll quickly move past that and provide some positive ideas for you or the accounts you manage, information that will make for better conversation during quarterly performance quarterly reviews.

Correct

for Deviation

Before checking on the accuracy of your decision-making tools, check on the fitness of the decider. You. Your aids for navigating the market may be in working order and just as useful as ever, but your ability to read them may be skewed.

There’s a fear center in our brains called the amygdala (/e’migdele/). The processing speed of the amygdala is 12 milliseconds (twelve-thousands of a second) if I convert this to a unit of measure to make it easier to understand, it equates to instantly. For example, if a bug lands on us (or if we see the words “market crash”) this fear center reacts and can instantly cause tense muscles, increased pulse rate, released hormones, and heightened sensitivity to anything else around that can be perceived as risk or danger. Have you ever experienced someone sneak up on you and cause you to jump? Your heart, breathing, and the rest of your body are instantly revved up. It takes a while to “recover” even after you know you’re okay. Your reaction processes changed in 12 milliseconds or instantly.

Think about all the information about health, markets, and economic collapse that has been heaped on us recently – within a short span of time. There are many reasons to expect our fear centers are doing what they were designed to do to serve our cave-dwelling ancestors. It’s taking over or, at the very least, weighing in on our decision making. When our amygdala is our co-pilot, we tend to question everything. The problem with this as an investor is it may not be measuring the next course of action rationally. It may be overriding our ability to measure one possible outcome over another. Prior to being hit with recent shocks, there may have been gloom and doomsayers that we could easily dismiss. This could have been TV News or other media that we knew was just trying to keep viewers’ attention, so we ignored any hype. We may have more easily accepted that there is always disease present in our lives, yet mankind has survived and thrived. We probably weren’t spending every day thinking, I better do something and I better do it now.

If you believe you are in the heightened fear mode and you’re concerned about the risk of your next move, try this: Turn off your TV and do these four things to help your mind reappraise the situation.

- Remove the personal side. Pretend you’re advising someone else. What advice would you give them? Then weigh the advice for yourself.

- Look at other times you or others were in similar positions. For the most recent stock market moves I brought myself back to the October 2002 plunge. This market event is the least talked about because it is the least remembered. It felt devastating at the time. I thrived afterward.

- Write down the three most upsetting things you feel about the future. Now mentally write a story, using actual acts available, that now develop into a bright future.

- Don’t immerse yourself in triggers. The most important quarantine for investors right now may be from others who are afraid. Fear is contagious and can fire up your amygdala.

Intelligent investors act out of patience and courage, not panic. If you are temporarily questioning your ability to act using your trusted tools and strategy, the focus should be on regaining that confidence, not acting despite it.

Move Forward Before it’s Completely Clear

I had read a New York Times article with the headline: Stock Market

ends its Worst Quarter Since 1987 Crash. The date on top of the newspaper was September 30, 2002. After the paper printed, over a couple of weeks, the market went even lower. Flash forward to this week, I have taken a lot of calls from investment advisors and even some big firm money managers. These are all veterans in the business, yet when I mentioned the Fall of 2002, very few had a recollection of those brutal few months. Storms pass.

The least popular advice anyone, especially with an activated amygdala, wants to hear is common sense. Investment axioms like: “Stay the course,” “The best time to buy is when there’s blood in the streets,” “if you liked it at $40 you should love it twice as much at $20,” are hard to swallow when you want quantitative reasons for your next move. Investors should base their decisions on hard data, not people just repeating what sounds good.

Here is hard data for you to review, not fluffy sayings: Statistically, as stocks decline, they become more dangerous. But, only in the short run. In the long-run, every leg lower equates to a higher probability of high returns later. On the surface, anecdotally, this makes sense, but it’s easier to get comfortable with if you see the data.

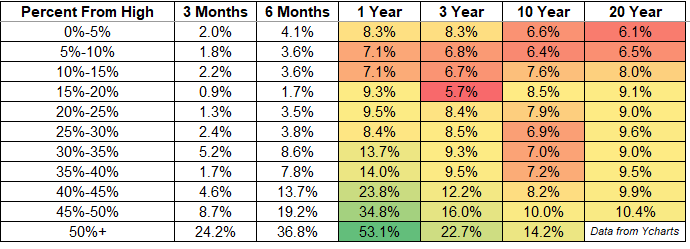

S&P Avg. Performance Since 1950 After Market Decline

The first column of the above table lists the stock market declines from their highs broken down into 5% increments. The next column shows where the market bounced to after three months; the next column lists 6-month results; this is then followed by average annualized returns for one, three, ten, and 20-year average annual return. Periods highlighted in green are above average; those in red indicate some decline from the previous period.

At the 20%-25% market decline level, and all further declines from there, there is a significant improvement in returns after one year. The average annual returns for all periods afterward are inline or better than returns expected by investors in the overall market. Based on this information, if you are in the market today, stay in. If you have cash, a better argument can be made for you to commit some of it than to stay away.

The above data is encouraging. It is important that I remind you that these are averages. Probabilities are nice, but what has happened in the absolute worst case is largely hidden in the data. The worst that has happened to any of these investors is information I would also want to review before committing capital.

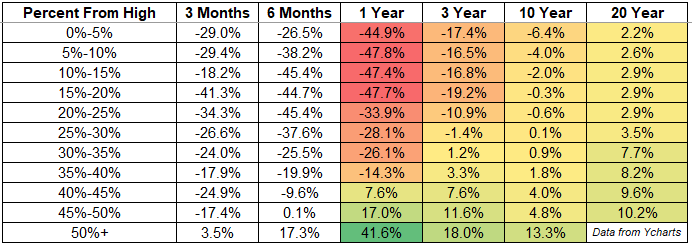

S&P Worst-Case Since 1950 After Market Decline

This new table is the same as the one above except it’s showing the single worst case of return as time went on. One take-away is stocks can go a lot lower over the short-term, but over the long-term, the situation starts to improve dramatically. With this as a guide, the worst-case scenarios have investors increasingly more at risk if they entered the market after only a small decline. In other words, since 1950, even in the worst-case scenario, investors have been better off when they have invested after substantial selloffs.

Checking the S&P level this Friday (3/20/20) I see the broader market is down 29.41% from its February 10th high. A Return to that level will require a mathematical increase of 41.70%. In the past, when we have been in this situation, the market has returned 8.5%-9.5% to investors after just one year. There is, however, the risk that history teaches us that we may have to wait longer than a year just to break even.

Paul Hoffman

Managing Editor

Suggested

Reading:

Exposure to these Sectors Could Enhance Risk-Adjusted Return

During the Recovery

Will Interest Rates Test Negative for Coronavirus

Bear Market Cycles, is it “Different” this Time

Sources:

Expressing

fear enhances sensory acquisition

Effects of

stress on decisions under uncertainty: A meta-analysis.