Image Credit: Image: Frankieleon (Flickr)

A Changing Dollar Value Impacts Investment Returns and US Inflation

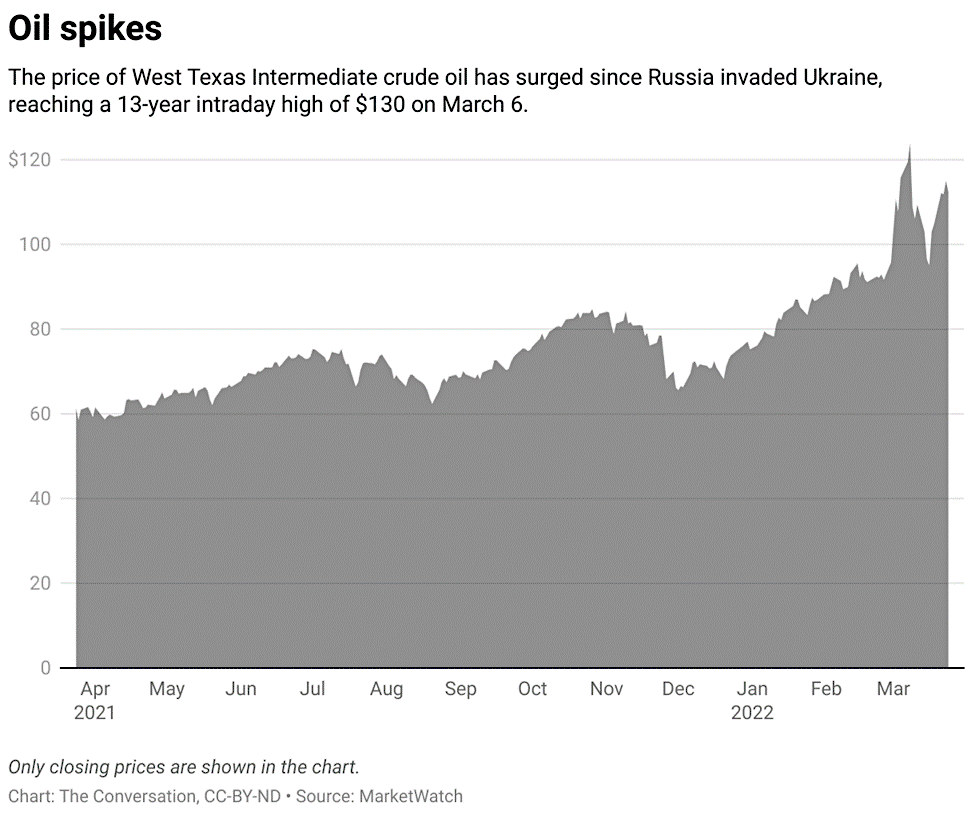

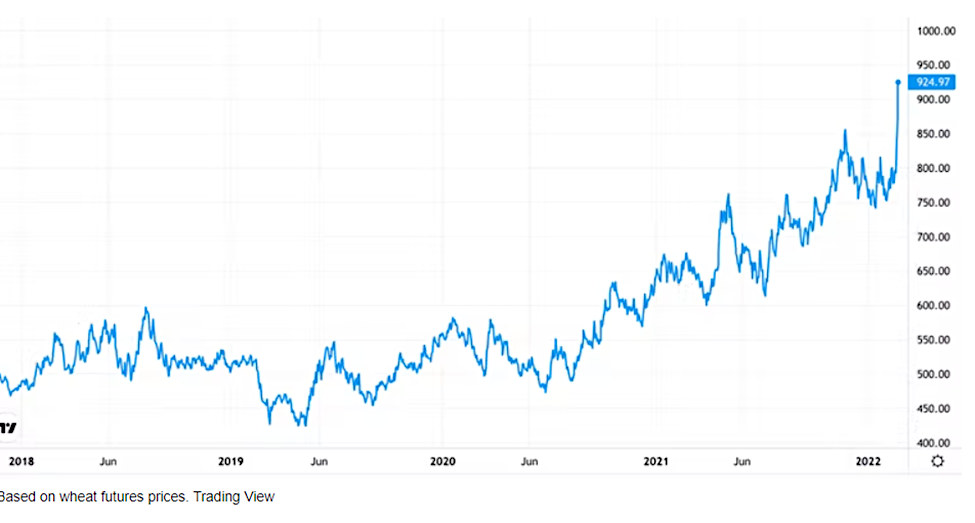

In his upcoming book, “Bonfire of the Sanities,” author and investment advisor David Wright warns that “actions have consequences” and that the move toward electric vehicles and the progression to eliminate reliance on fossil fuels could weaken the US dollar. In recent weeks his warnings are heightened by reports that China has been in discussions with Saudi Arabia to price barrels of oil in something other than dollars, in this case, the Chinese Yuan. If successful, how would US dollar-denominated investments fare?

Background

When the US took its currency off the gold

standard in the 1970s, it negotiated to tie greenbacks to energy in that most oil around the globe is bought and sold in US dollars. This, in effect, made dollars backed by oil, (petrodollars) and added constant demand for greenbacks which helped its strength relative to other currencies.

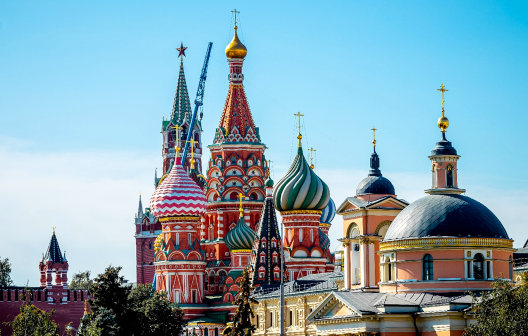

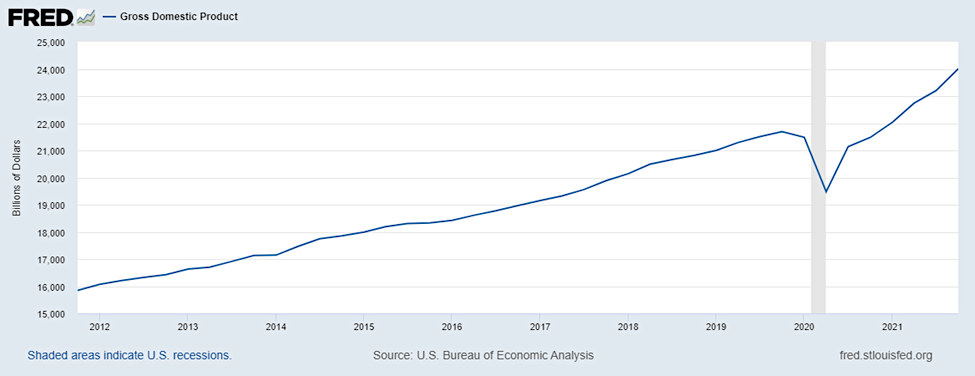

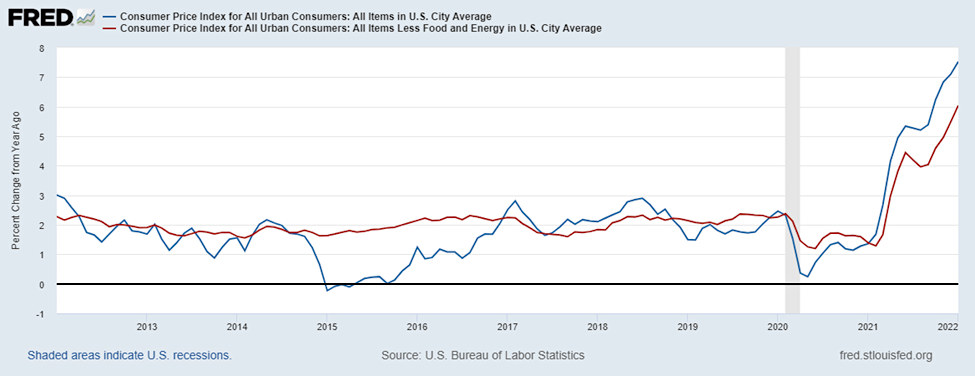

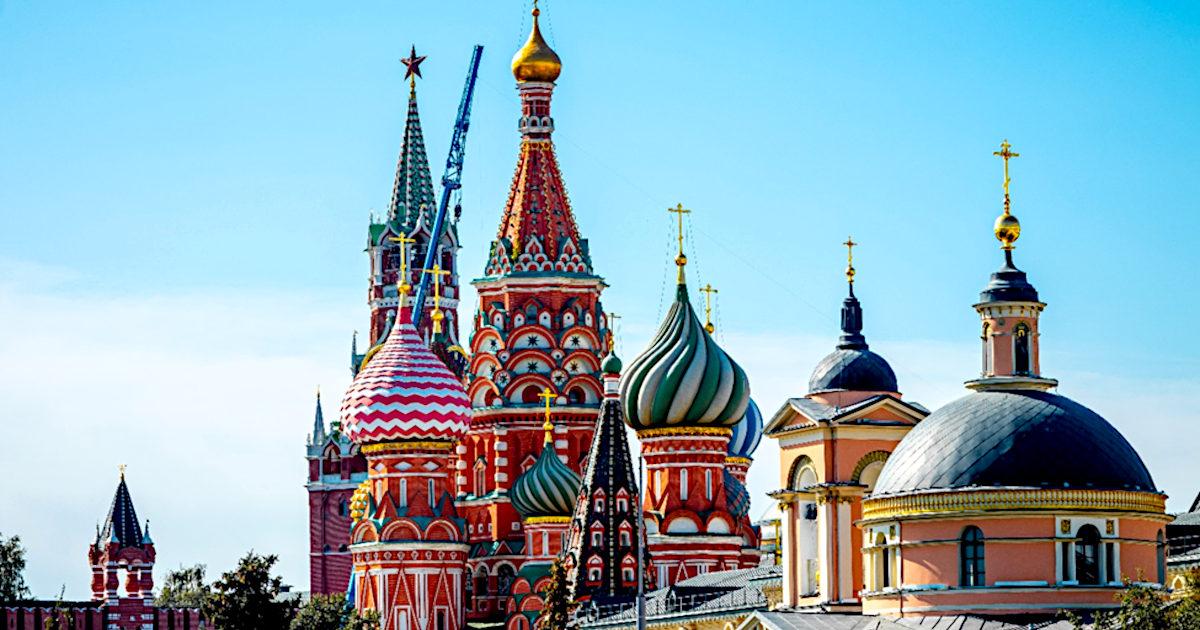

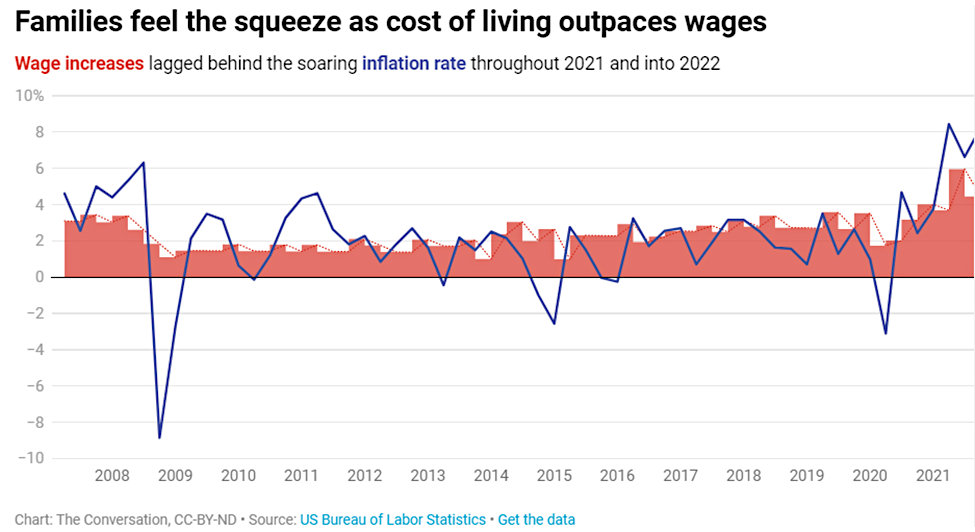

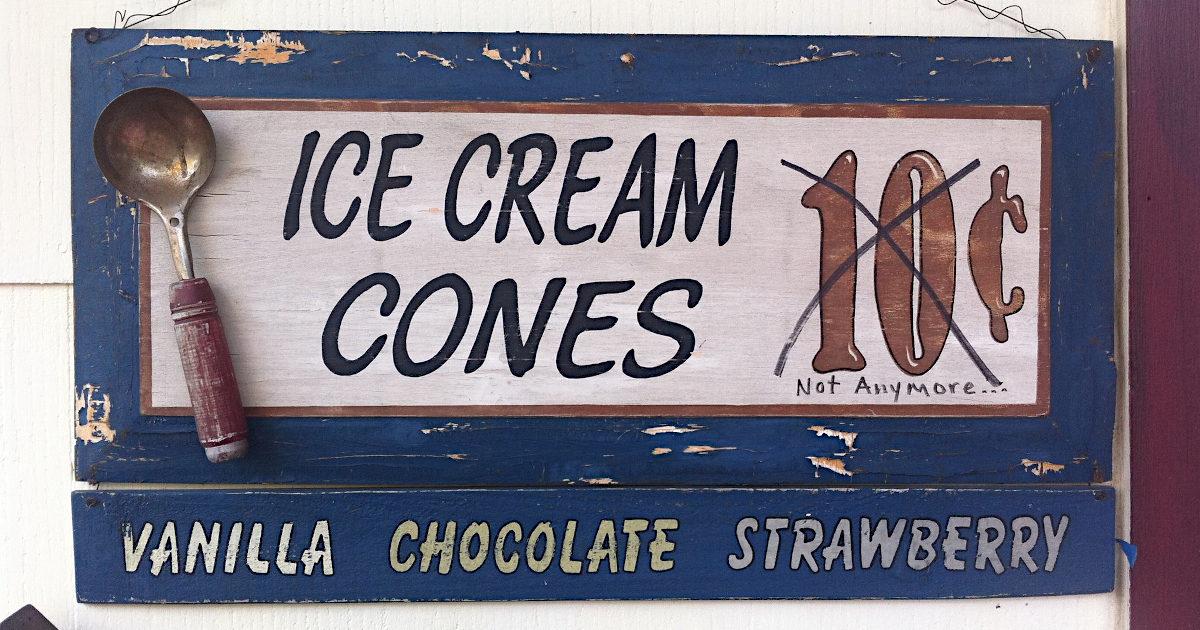

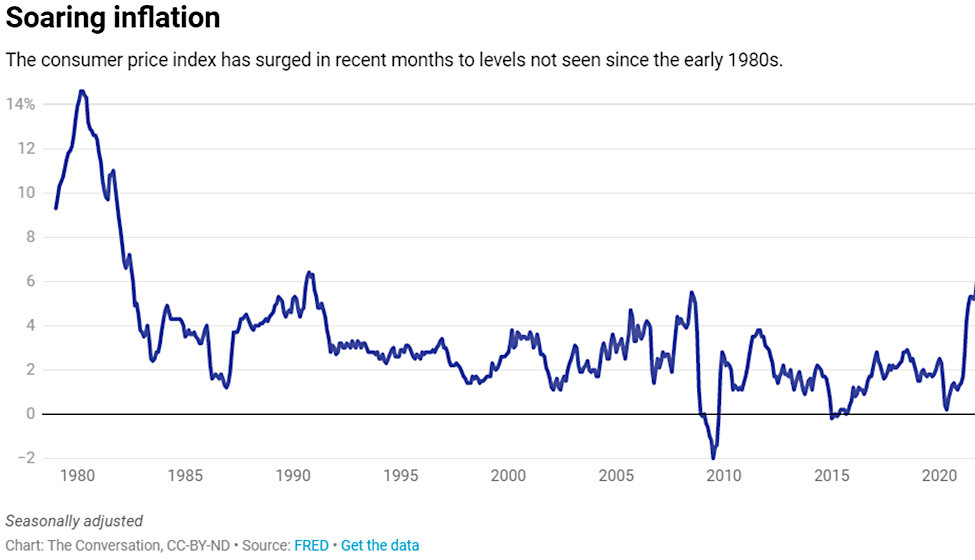

When the US imposed sanctions on Russian foreign currency holdings, the power and risks of relying on the US currency did not go unnoticed by other nations. China as reported recently took steps to have oil denominated in its own currency, the Yuan, which would likely add to higher demand for the Yuan while reducing demand for dollars. If China’s Yuan is “upgraded” in the world, it could in effect be seen as a downgrade to the US dollar. It could also cause a devaluation that translates into more inflationary

pressures and a reduced desire to own US assets, including stocks. Imports, especially from China could cost more.

Further impacting the dollar’s dominance, in recent weeks, Russia and India entered talks to enact a Ruble/Rupee exchange ledger for transactions. Moscow has also said Europe would have to use Rubles to pay for its natural gas and that it may consider Bitcoin as well. Fewer global transactions are taking place in dollars.

Potential Impact

Baizhu Chen a professor in the Clinical Finance and Business Economics department at the University of Southern California is quoted in Business Insider as saying, “The use of Chinese currency will inevitably expand and play a much bigger role in the world.” Chen explained, “Some countries feel their economies could be held hostage to US policies because the dollar is dominant, and countries want to diversify their risk.” So, while reduced demand for oil could play a role in valuation, current policies that use dollar-denominated finances have caused eyes to open to the risks of not diversifying currency use in financial dealings.

The Yuan has been gaining popularity. Approximately 70 central banks hold some yuan as a reserve currency, while many African and Middle Eastern nations have adopted it for transactions. Central banks, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), have been diversifying their holdings, and reducing the dollar’s share of global reserves.

“Were the dollar to lose its status as the world’s reserve currency, it would raise interest rates for our historically large debt relative to the economy,” warned Tomas Philipson, former Acting Chairman for the White House Council of Economic Advisers. This of course causes concern as it would mean US consumers and businesses would face higher borrowing costs along with higher import prices.

Current Status

For now, greenbacks comprise 60% of global reserves versus the yuan’s 2.5%. In global payments, the dollar accounts for 40% while the yuan has about 3%, even though China is the second-largest economy, trailing closely behind the US, Philipson said. That could change, but it would take massive reforms.

A More Competitive Yuan

China would have to open up its market and relax controls, according to Baizhu Chen. He noted that historically, no currency that has had heavy-handed control has become one of the dominant global reserve currencies. China would also need to refrain from currency manipulation. This takes place now in the form of devaluing the yuan to boost exports, according to Chen. This could be facilitated by allowing for an independent central bank with transparent decision-making.

In addition, the yuan must become as stable, reliable, and trustworthy as the dollar. “Countries generally trust that the US isn’t going to screw up. But whether the yuan could be perceived as a store of value — a safe haven during uncertainty or war — that is a much more difficult thing,” Chen said.

The current trend in China has been more control, not less. There have been signs that the government will ease up on its recent tech sector crackdown – the market (Chinese stocks) reacted positively. It’s uncertain whether this will lead toward more easing of control.

Managing Editor, Channelchek

Suggested Reading

Add This to the List of Inflation Drivers

|

Alternative Vehicle Fuel Types

|

Publicly Traded Chinese Companies Duty to Shareholders

|

The Case for More US Produced Uranium

|

Sources

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2022/01/25/world-economic-outlook-update-january-2022

https://www.imf.org/en/publications/weo

https://wrightfinancialgroup.com/resources/newsletter

Stay up to date. Follow us:

|