Image Credit: eFile989 (Flickr)

As Fed Promises to Orchestrate a Painful Bear Market for Bonds, Stocks Could Benefit

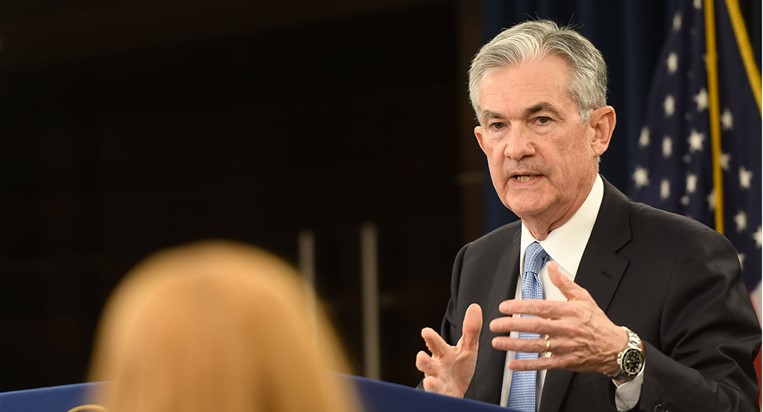

Occasionally I catch conversations on TV, in the press, and on blog sites questioning the Fed’s resolve to fight inflation. Many still wonder if an ongoing weak stock market will cause Chairman Powell to temper his proposed tightening pace. The Fed actually has no official concern over stock prices; however, it does formally try to maintain the stability of the financial system and contain potential crises. Since the value of the financial markets impacts wealth felt by households and capital available for businesses, an argument can be made that sinking the stock market runs counter to one of its three mandates. The fed’s other two mandates are to manage inflation and supervise and regulate the banking system.

This conversation came up the other day as I heard from my son-in-law after he was being advised to allocate more money into fixed-income investments and less to stocks. The reason given by his big-name advisor is that “stocks are entering a long-term bear market.” I personally don’t know if stocks are entering a prolonged bear market or not, but neither does his advisor, such things are not knowable except in the rear view mirror — months from now.

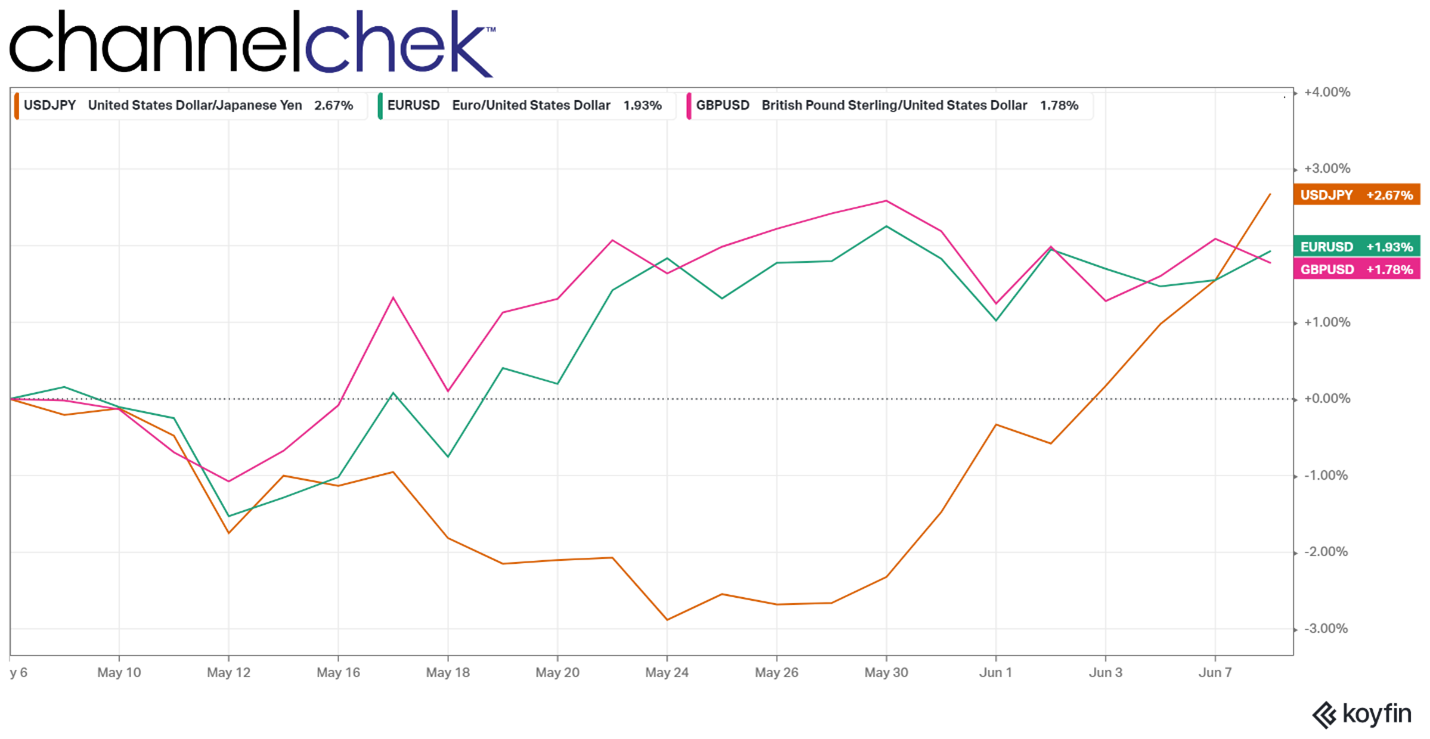

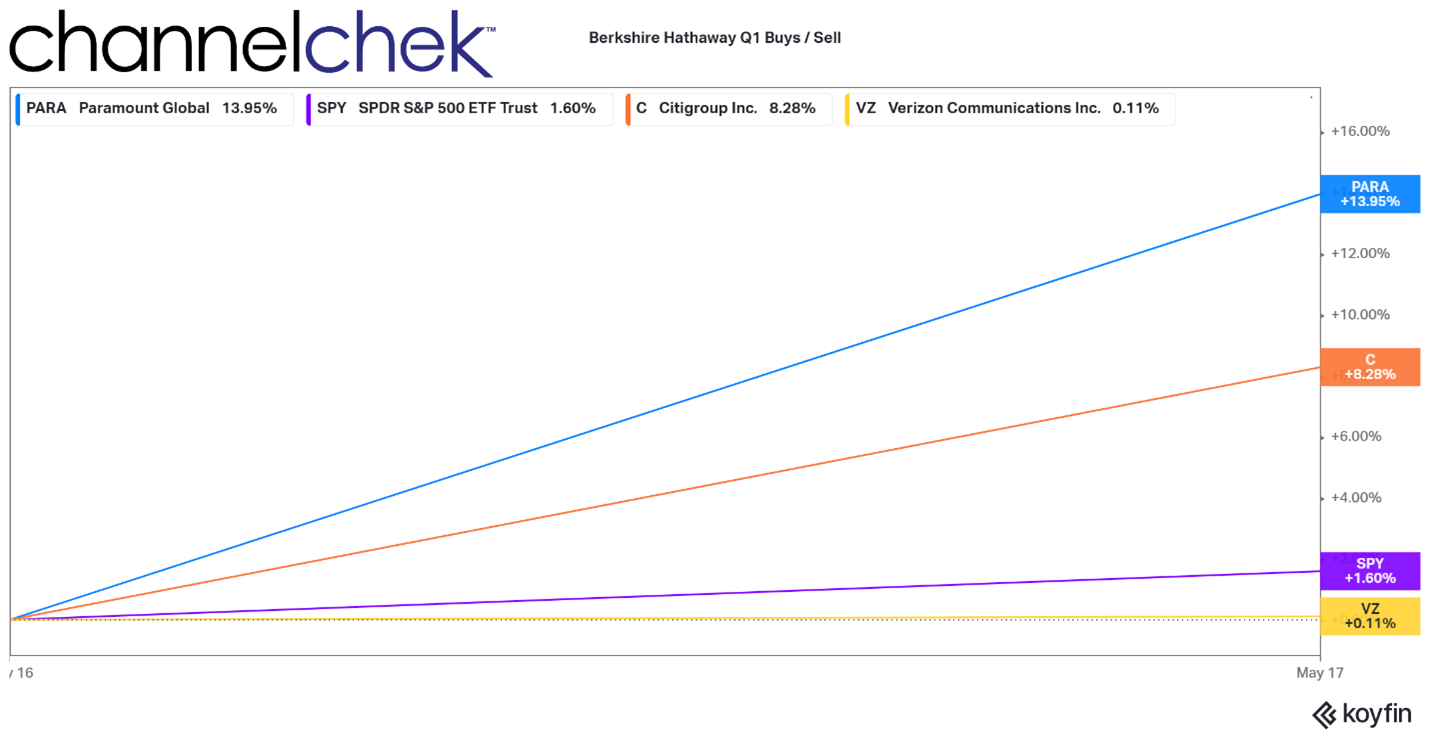

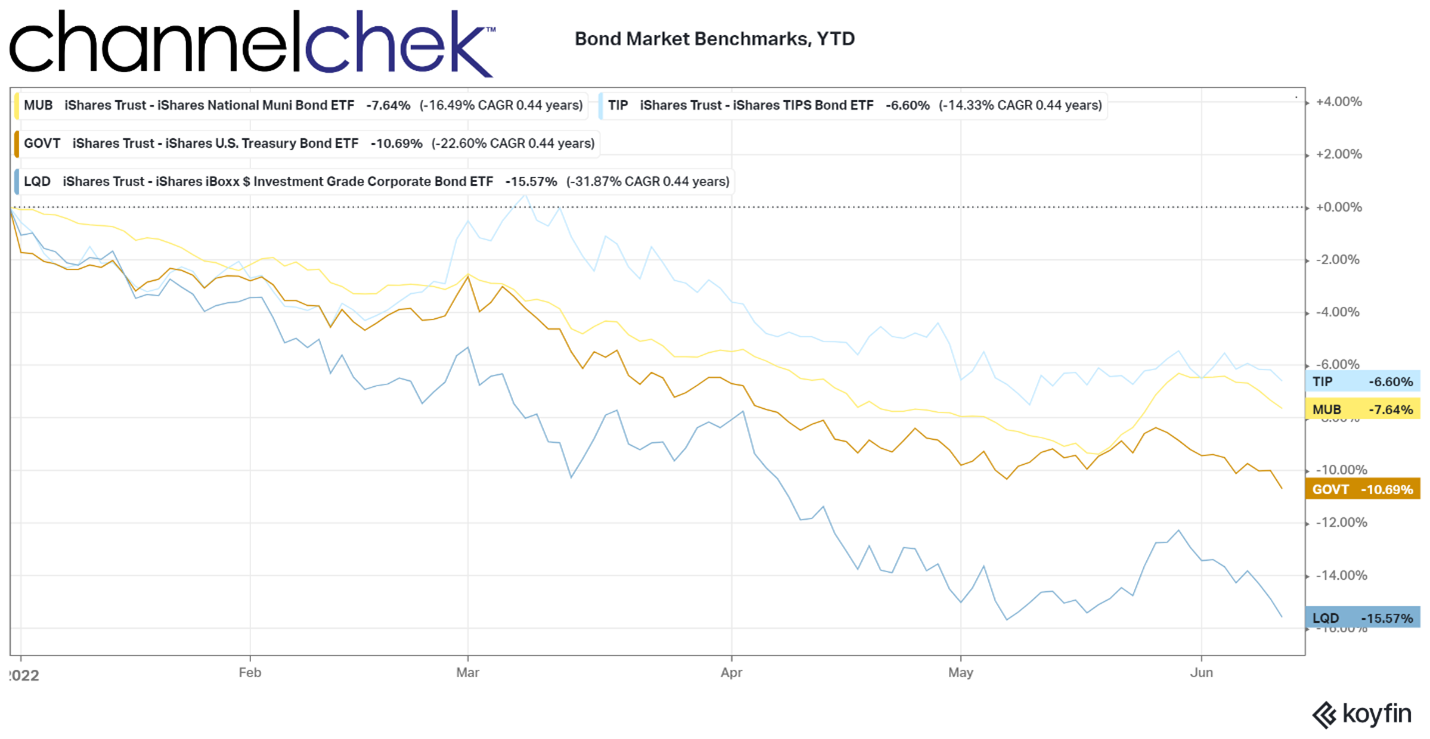

Source: Koyfin

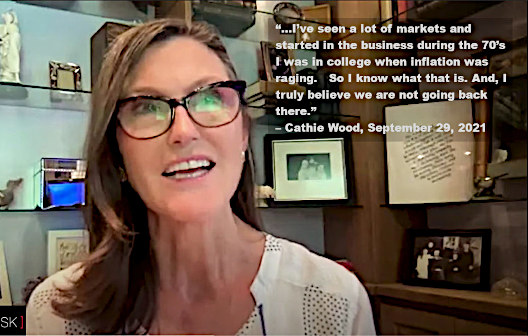

What is knowable is that the institution that controls the most investments on the planet has stated they are going to crush bond prices. Actually what they said was they will be raising interest rates for the foreseeable future until they bring inflation to less than one-fourth of where it is today. Higher rates are mathematically the exact same as crushing bond prices. And the Federal Reserve has an excellent record of keeping its promises over the past two decades. Transparency and clarity while doing exactly what they say they will do have been the Fed’s M/O under Bernanke, Yellen, and now Powell.

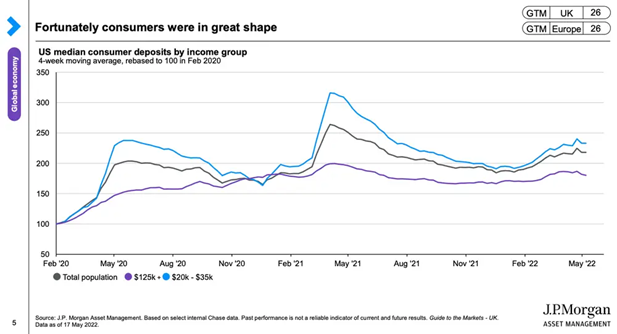

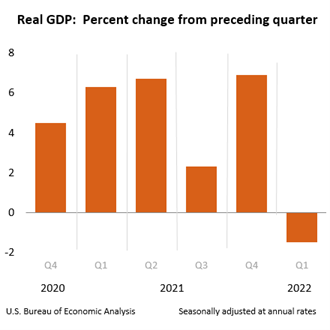

Why then, with negative returns like we see in the chart above, and promises that we are only at the beginning of the bond bear market would an advisor suggest interest-bearing securities? If the Fed does nothing you make 3%, if they do as promised you could easily lose 10% or much more in value.

At the start of 2022, the 10-year US treasury bond (UST10) had a yield of 1.70%, as of Friday (June 10) it hit 3.15%, which calculates to over a 13.3% decrease in price. Inflation was reported this week to be 8.60%, since we now have had a half year’s worth of data to know that inflation isn’t transitory, bond buyers will require a return of at least future expectations of inflation as their return. Is double the current yield of UST10 within the realm of possibilities? If inflation does not show signs of dropping dramatically it would be a historical oddity if it doesn’t rise to compensate investors for any loss in purchasing power while their money is tied up.

My son-in-law showed me the exact options that were recommended to him, they were bond funds, which have an even greater set of concerns, including taxes, coupon payments, and total return. I came to realize that I am making an argument for stocks. I’m not bullish on the stock market, there are companies I like, and industries that I’m exposed to, but the market as a whole mid-year 2022 is more uncertain than normal.

The returns shown above are for various bond proxies. Inflation-linked bonds are down 6.60% which means they have underperformed inflation by 15.2%. The poor retiree that bought these has reduced their purchasing power by over 15%. Municipal bonds are down a little more than TIPS, but not as much as government bonds which is interesting since the credit rating of US Treasuries is better. US Treasuries should continue to underperform as the Fed is conducting quantitative tightening along with monetary tightening. This directly impacts treasuries to the tune of $30 billion fewer held by the Fed each month for each June, July, and August. Then in September, they will begin reducing their treasury holdings by $60 billion each month. Hundreds of billions fewer treasuries will be held by the Fed by year-end, every dollar in par value looking for a new buyer. The treasury lost its biggest customer.

The last on this list is an ETF I used as a proxy for corporate bonds. Corporate bonds have been loosely tracking the stock market. Up in price when stocks are up, down when stocks are down. Corporates are quoted off their similar maturity treasury (spread to treasury yield), so the overall downward pressure on treasuries is a massive headwind for corporates even if stocks should begin to take flight in the second half of the year. The additional concern with the price movement in corporates is back when rates approached were near 1% in treasuries, many fixed-income buyers, including institutions and retirees, took on more risk to get more yield. As treasury yields rise, they can upgrade the overall credit quality of their portfolio.

Take Away

If we listen to what the Fed is telling us, and they have given us no reason not to trust them, bond yields will rise. Investors, particularly those in ETFs and bond funds, receive price changes as their return. When interest rates rise, prices go down. So far this year prices have sunk over 10% in US Gov’t bonds, and over 6.50% in TIPS, so-called Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities.

Anyone with money they want to invest that is avoiding the stock market or other asset classes like real estate, or commodities should consider that the bond market is the only asset class the very reliable Fed has told us they plan to beat up. A more advisable plan would be to selectively monitor companies and industries outside of fixed-income while they are cheaper than they have been in a while. Use Channelchek as a resource for evaluating small and microcap names, if you haven’t signed up for access to research, video content, and related articles here is the link to do it for free.

Managing Editor, Channelchek

Suggested Content

Small-Cap Stock Category Sees Most Insiders Buying Since Spring of 2020

|

Avoiding the Noise and Focusing on Managing Your Investments

|

Leveraged and Inverse ETF Do’s and Mostly Don’ts

|

Index Funds Still May Fall Apart over Time

|

Source

Stay up to date. Follow us:

|