|

|

|

|

A Cure For HIV Infection, Promise or Reality?

(Note: companies that

could be impacted by the content of this article are listed at the base of the

story [desktop version]. This article uses third-party references to provide a

bullish, bearish, and balanced point of view; sources are listed after the

Balanced section.)

Anti-retroviral therapy (ART), or highly-active-antiretroviral therapy (HAART), is effective in halting the progression of HIV infection (a disease affecting nearly 40 million persons worldwide). However, HAART does not cure the disease as the HIV virus, despite of the treatment, remains hidden in the human body. In 2018, Gilead’s Genvoya and GlaxoSmithKline’s Triumeq, the two top selling ART drugs, had annual sales of $4.62 billion and $3.36 billion, respectively. Notwithstanding their commercial success, these medicines do not cure the disease. The HIV virus often remains hidden in the human body in reservoirs such as dendritic cells, macrophages, and CD4+ lymphocytes. Resistance to treatment, side effects of HAART, stigma, and the cumbersome need for lifelong therapy are all important issues highlighting the need for a cure. If a patient interrupts antiretroviral therapy, the viral infection comes back. Since HIV was first detected in 1983, the medical community have intensively searched for a cure for this disease.

The Story of the Berlin

Patient

In 2007, Timothy Ray Brown, an American studying in Berlin, Germany, was treated with a hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Two years earlier, Mr. Brown had been diagnosed with a type of blood cancer known as acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Besides its cancer diagnosis, Timothy was infected with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Dr. Gero Hütter, a German doctor from the Charité Hospital, Berlin University of Medicine, performed the transplant. Before seeing Timothy, Dr. Hütter had never treated an HIV patient, but he had learned about a rare genetic mutation causing natural resistance to HIV infection. Based on this information, Dr. Hütter found a stem-cell donor carrying this specific mutation. He performed the transplant on Mr. Brown using these mutated cells.

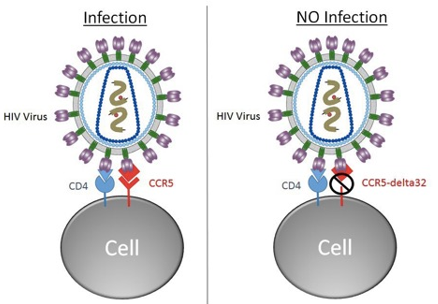

The procedure resulted in a surprising outcome. Timothy’s HIV infection disappeared after the transplant. The HIV virus could not be detected on his blood, not even with the most sensitive diagnostic techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods. Timothy Ray Brown was cured of his HIV infection. He became famous in the medical community. Timothy is now known as the Berlin patient. The story of the Berlin patient triggered significant interest in both academy and industry, setting off a gold rush to find a sterilizing cure for HIV infection. Timothy’s transplant treatment was done from a donor carrying a mutation in a gene known as CCR5, which happens to be the site of entry utilized by HIV virus to infect immune system cells (New England Journal of Medicine 2009, 360, 692-698). The CCR5 protein receptor is expressed on the surface of lymphocytes T, which are the primary cells targeted by HIV virus. Two cell receptors, CD4+ and CCR5, are utilized by HIV to enter the cell. The virus cannot enter and infect cells with a defective CCR5 receptor.

As a result of CCR5 mutation (no site of entry), HIV cannot find a home, the patient’s viral load gradually decreases, and eventually the virus fizzles out. This is probably what transpired during Mr. Brown’ treatment procedure. The virus became undetectable in Timothy’s body. He stopped taking any medication for HIV, although he continued to undergo treatment for his blood cancer. Timothy has remained HIV negative for 12 years now. He has been cured from his HIV infection.